[ad_1]

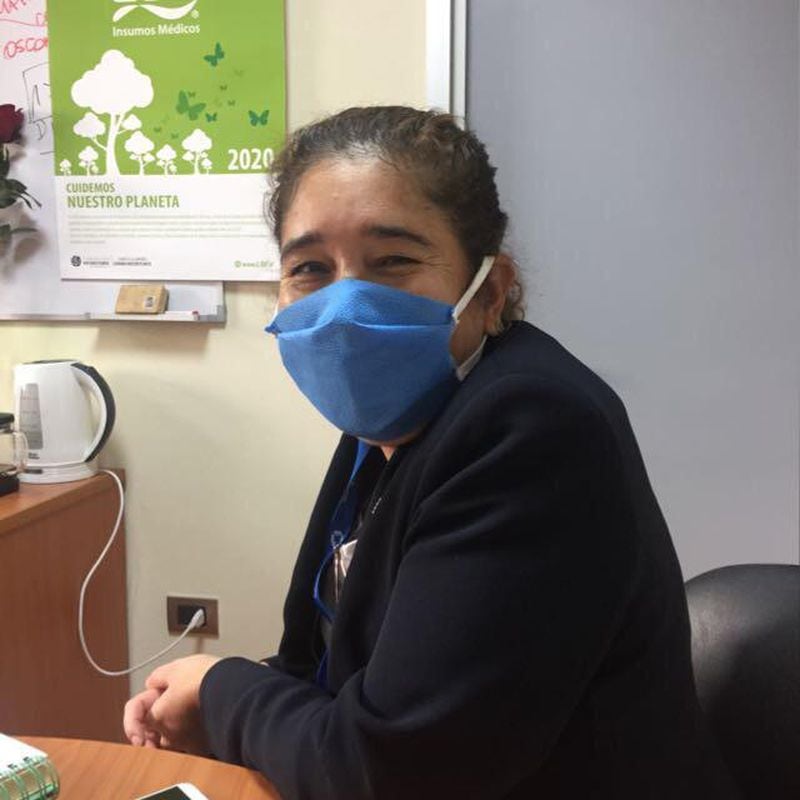

Nurse Maritza Seguel has built a successful career at Mutual de Seguridad. For 15 years he has been in charge of the head of the institution’s neurorehabilitation and general surgery surgical medical service, and on April 2 he added one more credential to his CV when he was handed the head of the Covid-19 service, after the Minsal will join mutual societies to the public sector to face the pandemic. In record time, the professional had to assemble the new unit, have between 15 to 20 beds, move the patients who were occupying them to other sectors and train the 66 members of her team. The procedure was successful, but it had a special and different nuance at the same time.

“When they told me that I had to take over the service, for me it was strong, because I thought‘ if I have to encourage this team that is afraid just like me, I have to show that this does not impact me as much because I cannot transmit fear to others’. It is a challenge, but it is a beautiful challenge ”, Seguel acknowledges.

That fear that the nurse mentions is the same that is present today in the different hospital centers of the country that must attend to the growing number of Covid-19 patients. While the rest of the population tries to stay at home to avoid exposing itself to the virus, it is the doctors, nurses, technicians, administrative and auxiliary personnel who have had to swell the “front line” of Chilean health.

“The day we opened as a team to serve Covid-19 patients, it had an impact on the entire team and fear was generated. Some of the staff said ‘I don’t feel ready’, ‘I’m afraid’, ‘I don’t want to get infected, I have children’ ”, says Nurse Seguel, who believes that in a profession like yours, knowing how to manage emotions is very relevant. “When your job is to treat the other, one tends to hide their feelings, or to block them, because I cannot transmit to my patients an emotion that is limiting you, such as fear,” he says.

To prevent this reaction, plus the heavy workloads or the same cases of discrimination against health personnel that have been reported in recent weeks, from affecting their workers, medical centers have established emotional support programs and self-care protocols. . These initiatives are led by psychologists who have become the main support of the “front line” of health, making interventions by video calls or telephone, in order to control symptoms of anxiety, anxiety or sometimes more severe pathologies that arise from the tension and uncertainty caused by the pandemic.

Pablo Barraza, nurse of the Critical Patients Unit (UPC) of the Sótero del Río Hospital:

“There is staff stress and fear, fears of their own too, everyone has their history, their relatives and going through this is not an easy thing. You can’t digest the emotion and you have to be attending and attending well. We are going through a very high stress and probably in some people this triggers other things, we have to take care of ourselves because perhaps when we lower the intensity it will be late for some. “

José Arancibia, head of the organizational development unit of the Sótero del Río Hospital, cannot give names, hospital units or ages, since his work is governed by confidentiality rules that prevent him from doing so. But he still remembers the case and the anguish of an official who works as an administrative officer in the hospital’s clinical area, permanently surrounded by doctors and nurses.

“He told me that he was afraid of going crazy, because he was not sleeping well and had recurring thoughts of infecting his family or dying. By talking, you realized his anxiety and lack of control,” recalls the psychologist, who says that in Sótero del Río They have been working for two months in activities where they provide counseling and psychological tips for staff to face this period of pandemic, in addition to personal mental health consultations, where Arancibia has registered five other cases of containment and a couple of referrals to the center. of internal care of the hospital in order to follow a psychological treatment. “There are three great fears within the staff: going crazy, dying and being a source of contagion for the family”, says Arancibia about what has been observed in the program.

Such stories are heard daily in the Crisis Intervention Unit (UIC) of the Chilean Security Association (ACHS). The group was created five years ago by Nélida Riveros, who says that there are 52 psychologists who are experts in working during catastrophes or highly complex work situations. “We define ourselves as a herd of support”, Riveros tells about the team that works assigned in private clinics and health services in different parts of Santiago and regions.

“For this pandemic we realized that we had to make a turn and we developed a special program to help medical teams that are on the front line today, such as emergency and urgent teams,” explains the psychologist. In their work they use the frameworks Theorists from the WHO and the Red Cross, and usually deal with video calls.

Nicolás Montecinos, kinesiologist UTI CLC:

“The most difficult thing is to be away from loved ones. Staff working in intensive care are prepared for stress, for challenge, but doing it alone, without emotional support, is different. We all studied, we all sat down to read, but nobody told us that at the end of the day we would not have the family. ”

Their work is carried out under two modalities: preparing medical team leaders to detect emotional problems in their groups and remote personal interventions, which are the most required. Riveros says that they left the first week of March with 10 cases and by the middle of that month they had almost 200. Today they are doing some 600 interventions, of which 95% correspond to health service workers, while the rest belongs to ACHS member companies that cannot work remotely, as is the case with supermarkets.

Riveros’ unit is used to doing their work many times after office hours or on weekends, when their patients have time at home to take the time that on average lasts each session. “It is calculated so that the psychologist can make a good intervention, not that it is a 10-minute thing. We communicate with the collaborator and We work with him on his sources of concern and anxiety at a personal, family or work level ”Riveros explains.

At the Las Condes Clinic they must also juggle the times. There they launched “Take care of us”, a program that provides tips to take care of the emotional health of workers. The establishment’s psychologists volunteered to provide remote attention to all officials who needed it.

“People when they are in the clinic work, so it is difficult to make contact there and it has to be from home, in their free time. These remote interventions are learning for me, because we are living a situation that no one ever imagined living, and as psychologists we did not do it either. At first it costs, but you have to adapt, ”says Verónica Robert, who works at the Cancer Institute of the Las Condes Clinic and is the head of the psychology unit of that institution.

Leticia Méndez, Paramedic Technician at the ICU Hospital in Temuco:

“We are afraid, afraid of the unknown, afraid of getting sick, afraid of infecting our families. At the beginning the stress and the work rhythm was very tired, very exhausted and we talked among the colleagues that although we got home very tired we could not sleep ”.

A similar program has the German Clinic, where, in addition to emotional restraint lines for officials and a plan especially dedicated to the front line, this week another one was opened to contain the families of professionals who often stop seeing them for fear to contagion. “We were detecting fear and anguish in the children of the workers and as a result we launched this initiative where the same psychologists, psychiatrists, occupational therapists and psychopedagogues at the clinic made their services available. They have contacted us a lot, they say they need support or tips to see how to manage it with their relatives. An example is children, who are suddenly more anxious “, explains psychologist Marcela Apablaza, head of culture and development at the German Clinic.

In other establishments, the containment process has occurred among the coworkers themselves. Myriam Gálvez, deputy director of the nursing area of the Mutual de Seguridad, says that since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis she has seen very anxious medical personnel, a reaction that dissipates with the passing of days, but that is reactivated with each new patient. “The first thing is the anguish that immediately reaches the nurse on duty or the head nurse. She must remain calm, ”he says.

This fear has recurring causes that affect all classes. In Sótero del Río, Darling Salgado -psychologist from the hospital’s workplace coexistence area- clarifies that psychological containment has been required “by all levels, from assistants to administrative and professional. The most recurrent fear is getting and infecting their families or patients. ”

Despite these apprehensions, the staff continues to carry out its duties. “Regardless of all fears, they want to do their jobs. That leaves me feeling very hopefulRiveros says.

“We have the feeling that a great wave is coming. But that critical situation, which is when we have to receive the overflow of public health patients, does not come. It is a situation that generates a lot of anxiety ”. The phrase -from the psychologist Bárbara Guzmán, head of training and development at the Las Condes Clinic- portrays another factor that shakes mental health in Chilean hospitals today: the scenes of collapse of health systems in Europe and the United States. United and threatening to repeat themselves in Chile.

Fernanda Meneses, geriatrician, National Institute of Geriatrics:

“The emotional charge is enormous, I believe that none of us when this is over will continue to be the same, this will produce changes, make us mature, make us know other facets of us personally and professionally as well. By working with the highest risk group, we know that a significant percentage of them will not succeed and that is the strongest. “

It is a scene that could happen in the short term. “What is coming is anticipatory anxiety. There is the question of how we are going to do it or if they are going to reach the resources in the face of the emergency, ”says Riveros, about this feeling that is seen both in the UCI and UTI teams, and in the administrative staff that today must remain. in clinics and hospitals.

It is an alert state where the body releases cortisol, the stress hormone that cascades what is known as allostatic load: the physical impact of being constantly on alert continues to accustom the body to living under this overload, but imbalancing the ability to face the tension. Something that according to psychiatrist Constanza Caneo, from the UC CHRISTUS Health network, can be as good as it is bad: “What tends to happen after a while is that the mind adapts to this new normality,” explains the professional, adding That is how adaptation, resilience skills are developed and people are “equipping themselves” to face uncertainty.

To face this scenario, two weeks ago, the UC CHRISTUS Health Network made the “Safe Place” program available to its workers, the same one they used for social outburst, but now on a website. There they added mental health professionals to support the teams, although so far they have only received 20 consultations, none of them from the first line, such as emergency doctors. “I have a preliminary feeling that they are not properly identifying themselves yet. They are distraught and worried, but not necessarily unarmed to pick up the phone and say so. “Caneo says.

The psychiatrist explains that the difficult thing in these cases is that, although she believes that they may need help, they still cannot intervene because a simple question such as “are you okay?” Can play against them by bringing an implicit evaluation. “We cannot induce them to think that they are in crisis, because when someone really is, they are dissociated, but working because they realize that a patient may die and it may be their fault if they do not work,” says the psychiatrist.

This is complex considering that hospital workers have few mental avenues of escape from their jobs. “We are 45 hours a week thinking about the Covid-19 and then you go out and keep thinking about the same thing because the environment leads you to keep talking about it. So, you are seven days a week talking about your work, “says José Arancibia.

Carolina Vásquez, Hospital Internist at Temuco Hospital:

“Normally we do the technical part, we give some support to the patient, but now we are the only human beings who are next to the person who is suffering. That emotional part is usually supplied by the family, they accompany them, they take their hands, they give them encouragement and now we are the only ones who can grant them that. Trying to contain, to give encouragement, to be the ‘family’, is very shocking and is an emotional burden for the health personnel ”.

That is why containment programs aim to avoid the feared equipment burnout, a physical and mental exhaustion for work reasons. For this, a series of recommendations are made to medical personnel, such as that they should drink water frequently, eat at the appropriate times, go to the bathroom and sleep. The idea is that they comply with the modern Hippocratic oath where they swear not only to take care of the rest, but also to themselves, precisely in order to be in good condition and help others.

“There is no use the burned, desolate or addicted doctor. He is not going to do his job well, as much as he is a tremendous professional. The first thing is to promote self-care, “says Caneo, who says in the UC health network they train the heads of services to recognize the burnout on their computers, detecting if someone begins to be disconnected, to have behavioral changes or to make consecutive errors such as misspelling a prescription, which in hospital jargon they call “sentinels”. “If a doctor commits two consecutive sentinels, he deserves someone to approach him in a friendly way, because that person is not in an emotional condition to be able to function,” explains Caneo.

These days there are several scenes that induce you to make those unforced errors. One is people who fall hospitalized by Covid and cannot be in contact with their loved ones, so they are left alone. “Today the health personnel are fulfilling the role of the family, in the sense of giving support to the patient,” says Guzmán.

That experience of being the last link of people who may die has for some psychologists a double reading. “It can be hard or also a privilege to accompany someone who cannot be with their relatives”, says Verónica Robert. For her it is a situation that is only going to finish pondering once the pandemic passes. “Later, it will be necessary to make sense of all this and realize that perhaps it was a privilege to have accompanied those people at that time,” he says.

Amelia Góngora, CLC coordinating nurse:

“The workers are always anxious, but very enthusiastic. The most difficult part is the emotional part, we continue to train ourselves every day, learning, simulating and preparing for the worst. The stress has gone down, but now the anguish we feel is not knowing when and how the virus will peak in the country. “

This, because although medical personnel are trained in their training to face periods of great tension, such as the death of a patient, many times that instruction is not enough. “That happens with nurses, who are people trained for this type of contingencies, such as earthquakes or tsunamis, but when in this context they are already requiring instances of containment, it is a reflection that as a team they are feeling the weight,” says Arancibia.

Others go further and suggest that there are situations for which you are simply never sufficiently trained. “They prepare us all, but we are not so prepared. Although we are prepared to know that there are patients who may die, in the context of this pandemic, with the levels of death seen in Europe, nobody is so ready “Riveros says.

Along these lines, it is too ambitious for psychologists to think that someone can be completely “emotionally equipped” in order to face such difficult scenarios. “Many basically need to be listened to, and from there one can propose an intervention that makes sense to the person, but one of the main things is to be listened to,” says Arancibia.

As for the cases of medical personnel discriminated against by neighbors, such as those reported in recent weeks on social networks, psychologists rule out having seen them a lot in their interventions. “Hopefully we have found three cases like this”, says Riveros, who says that, on the contrary, his patients tell them of many gestures of citizen gratitude that end up being the great engine of the first line: “Generally, the negative act is discussed a lot, but there are many solidarity and they are very grateful for these gestures from people. For one negative thing, there are fifty positive ones ”.

[ad_2]