Late last year, the FCC ruled that U.S. carriers were exaggerating coverage and speeds in their cards – which literally anyone with a phone call in the US can attest to. While the blame flew back and forth (the carriers tried to pinpoint this seriously as a regulatory issue, you can not create this), the FCC calls for even better testing for more accurate maps. But now both AT&T and T-Mobile are stepping up from light marketing rhetoric to legal rhetoric, and formally objecting to the plan as said, claiming it would cost them too much, and that fairer testing might confuse customers one way or another.

As detected by Ars Technica, objections from both AT&T and T-Mobile were filed on the 17th and 18th, respectively, in response to an FCC proposal that carriers provide better evidence of coverage with real-time “drive testing” back in July Verizon last year also objected to details regarding real-world testing, hoping that better quality testing could pinpoint the underlying gaps in rural broadband.

In its complaint, AT&T claims that “it is not possible for all carriers to use the same parameters and produce cards that accurately predict their individual network performance.” That’s an argument that can hold weight, except that the parameter in question is things as simple as “speed.” AT&T also claims that the hassle and cost of producing these cards outweighs any perceived benefit – probably the large consumer level ignores more realistic cards clearly provide. And T-Mobile agrees: “Doing so would only impose more burdens on providers and lead to further customer trust without providing a proportionate advantage.” As far as I can tell, that speaks bullishit for, “like, that can cost money, man. And then customers might realize that our cards are lying. And an honest card is for them a lot more confusing than just having problems in an area that we claim to serve. “

Some other objections by the carriers hold weight, though, such as concerns about standardizing test methodology when it comes to testing resolution and “challenge” (as a result) types, in a way that does not detract from a specific network architecture. But those are details that can be worked out.

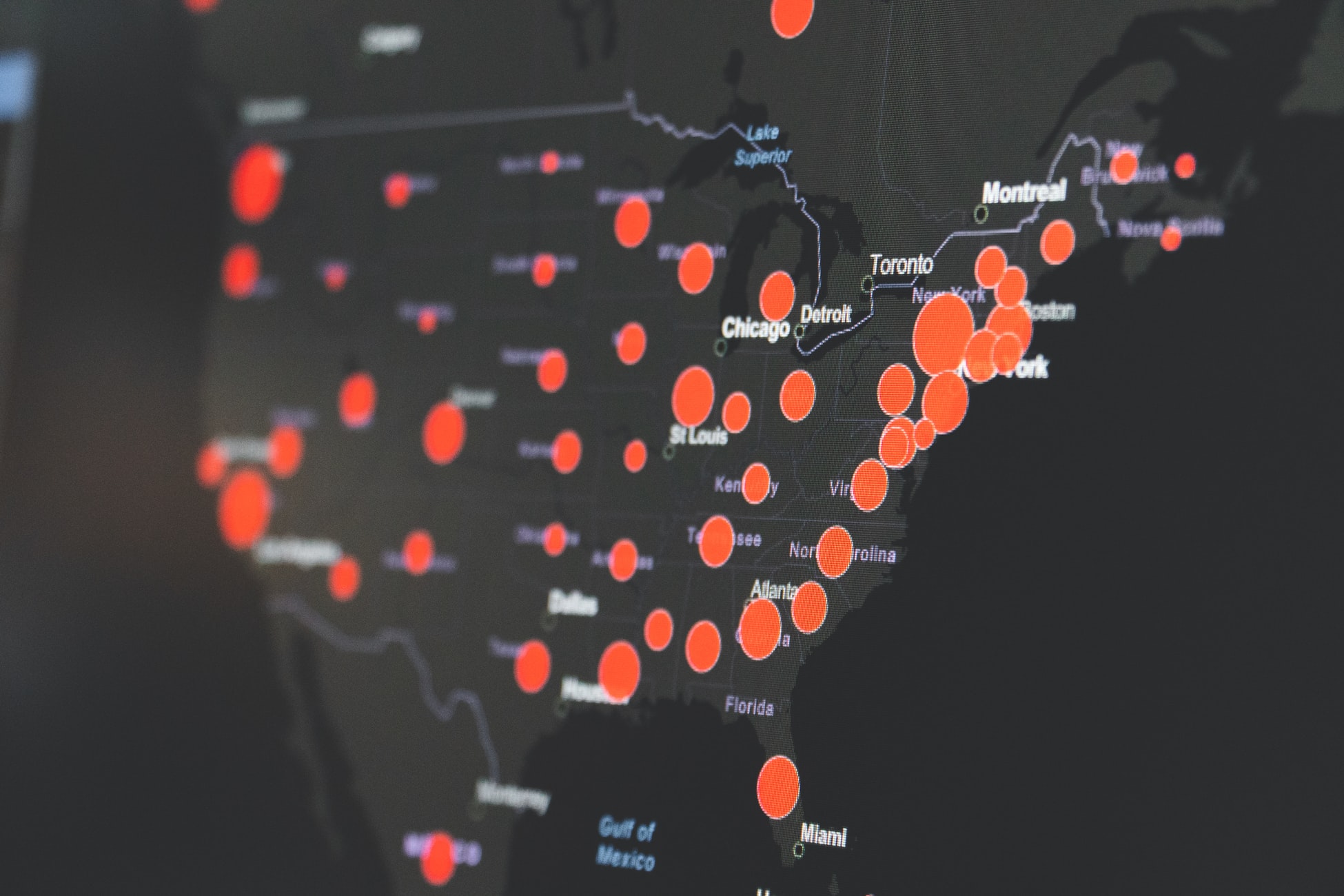

Map by the California Public Utilities Commission that compares propaganda models with results around the world.

At the moment, most cards out there are purely based on how the signal is expect propagate under ideal conditions – spherical cows in a vacuum-type substance. But numbers in the real world rarely reflect that, making those cards a best-case scenario that you will almost never see. In places with a ton of strong coverage it is not very hot, but in rural areas the difference can make an enormous belly. And this is not just a bunch of eggheads bickering over model differences, we all have anecdotally similar problems with little or no signal in an area that claims to serve our transportation cards – it’s a in fact problem.

The FCC can still change its mind about these tests as roles when it comes to mapping in the real world, now that carriers have more formal objections to it. The agency has not been as strong with U.S. carriers as it once was, and it shone over this mapping issue last year, and chose not to punish carriers for misleading the public and misleading federal funds.