Jelly Belly, Kanye West’s clothing company Yeezy and the SETI Institute, which seeks extraterrestrial life, are all California companies that received millions in loans from the federal coronavirus relief program for small businesses, according to data released by the Trump administration on Monday.

The federal government has distributed more than $ 68 billion to a wide and eclectic range of 580,000 California companies in the past three months as part of the Paycheck Protection Program, which offers loans to companies with 500 or fewer employees that can be forgiven if the employer meets certain requirements. criteria, including the use of money to keep pre-pandemic employees on the payroll for at least eight weeks after receiving the loan.

The majority, more than $ 50 billion, went to a subset of 87,000 California companies that received loans of $ 150,000 or more. The largest loans, in the range of $ 5 million to $ 10 million, went to just 647 companies in the state. Manufacturing and construction companies received the highest percentage of those loans in California, but few parts of the economy remained intact, and money flowed to law firms, technology companies, film studios, healthcare companies, farms, hotels , restaurants and even a three-in-three basketball league founded by rapper and actor Ice Cube.

The Trump administration’s release of more detailed data on PPP borrowers, including the identities of those who raised $ 150,000 or more, came after mounting pressure from Democrats and various private groups demanding more transparency around the program. of loans of approximately $ 660 billion.

But within hours of data release, California companies were contesting accuracy. Santa Monica scooter company Bird Rides Inc. is on the government’s data list for having received a $ 5 million to $ 10 million loan in late April. But in a statement, the company said it never applied for or received a PPP loan, and CEO Travis VanderZanden tweeted that the company is speaking to his bank and investigating how it ended up on the list.

Taking the federal data to the letter, the loan recipients said the money would go to support more than 6.5 million jobs, or about 37% of the state’s total jobs in February, before the economic effects of COVID-19 The pandemic began. But it is too early to say what percentage of those jobs were actually saved by the federal program, which will allow companies to forego paying loans at an interest rate of 1% in the next 24 months.

Notable companies that received loans in excess of $ 5 million, according to the data, include the online personalized gift market Zazzle, Aladdin Bail Bonds and Cacique, the Monrovia-based meat and cheese company.

Several nonprofits also received loans in excess of $ 5 million: various Planned Parenthood health centers, the Huntington Library and Museum in San Marino, and numerous religious organizations, such as the Catholic Diocese of San Bernardino. In the $ 350,000 to $ 2 million loan range, the Ayn Rand Institute in Santa Ana received a loan, as did the Foundation for National Progress, which publishes the left-wing magazine Mother Jones.

The construction sector, including multi-family home developers, electrical contractors, drywall companies, and concrete and pipeline companies, among others, was the largest recipient of loans in the entire state, including 86 in the $ 5 range. million to $ 10 million.

The Los Angeles entertainment industry, which has been holding back concerts, sporting events, and TV and movie production due to coronavirus precautions, has come up with PPP loans to avoid layoffs.

Jim Henson Co. received about $ 2 million in loans to keep 75 jobs, for example, and the Gersh Agency received a top-tier loan in the range of $ 5 million to $ 10 million to help retain 250 jobs. Culver City-based Jukin Media, which makes money from viral video rights, said it applied for a $ 2.2 million PPP loan to cover the payroll costs of its 127 full-time staff and avoid layoffs.

Ice Cube’s professional basketball league Big 3 initially received a $ 1.6 million PPP loan, according to a Big 3 spokesperson. The Los Angeles-based league repaid $ 700,000 of the PPP loan after it decided in May to cancel the 2020 season. , and used the remaining $ 900,000 for operating and payroll expenses for more than 100 coaches, players and staff members, a Big 3 spokesperson said.

Food and hospitality companies, which saw business stop abruptly as requests to stay home took effect in late March and world tourism slowed, also made up a large portion of California’s loan recipients. .

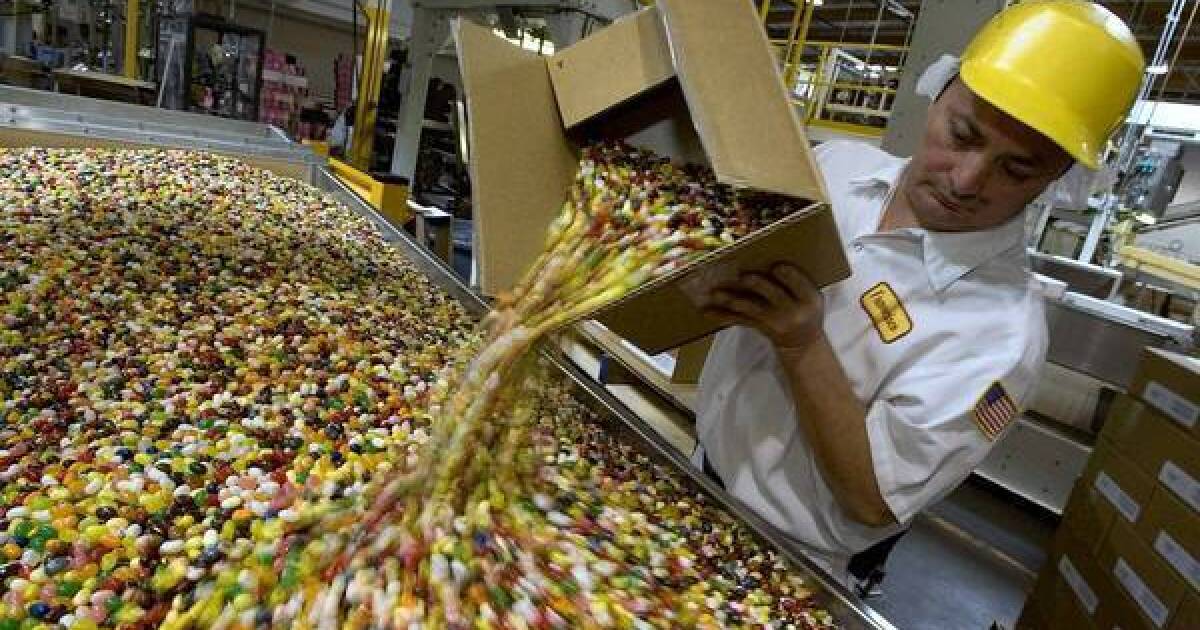

Jelly Bean maker Jelly Belly Candy Co. received a PPP loan ranging from $ 5 million to $ 10 million. The Fairfield, California company said in its statement that it applied for the loan “in good faith” and met all the requirements of the United States Treasury. Jelly Belly said the money was used to retain employees and that without the loan, the company would have had to “downsize” at the start of the pandemic. The money helped retain 500 jobs, according to SBA data.

A variety of restaurants in the Los Angeles area received loans, including mid-market chains like Norms, an iconic Los Angeles-area restaurant founded in 1949 that received between $ 5 and $ 10 million. But dozens of smaller restaurants, like Le Petit Greek, in the Larchmont neighborhood, which receives $ 150,000 to $ 350,000, also received federal aid.

And wineries like Plumpjack Management Group, one of Governor Gavin Newsom’s hospitality company properties, also received federal aid. He received between $ 150,000 and $ 350,000 in funds, according to federal records. Larger operations such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Geyserville distribution received loans in the range of $ 5 million to $ 10 million.

Newsom was asked about funding on Monday during a daily briefing on the COVID-19 pandemic and offered a brief response. “You would have to ask the people who run those businesses in a blind trust. Period. End point, ”Newsom said.

In a statement, the Plumpjack group said the loan enabled it to rehire a number of otherwise unemployed employees, adding that “like many in the hospitality business, our businesses have been struggling to survive during the Covid-19 crisis. “

A Beverly Hills hotel company owned by the Sultan of Brunei also received a large loan from the program. Kava Holdings, which operates as the Bel-Air Hotel in Beverly Hills and is owned by the Sultan of Brunei through the Brunei Investment Agency, an arm of the Brunei government, received a loan of $ 2 million to $ 5 million.

Forbes has rated Hassanal Bolkiah, the Sultan of Brunei, with a net worth of approximately $ 20 billion.

“I am shocked and outraged that one of the richest men in the world got millions from our government to keep his hotel open,” said Kurt Petersen, organizer of Unite Here Local 11, represents 32,000 workers in hotels, restaurants, airports, sports stadiums, and convention centers in Southern California and Arizona. “There should have been some due diligence on who is going to receive that money.” The hotel’s parent company declined to comment.

The PPP program has faced criticism of its execution and responsibility since it began. Initial PPP funds of $ 350 billion were exhausted in approximately two weeks, and it emerged that some large, publicly traded companies took advantage of the program, effectively excluding needy small employers until Congress reinstated the program. .

The Treasury and Small Business Administration did not provide a list of all borrowers who had returned or canceled PPP loans, but a senior administration official said more than $ 30 billion of the funds have been returned or canceled, including loans to Los Angeles. Lakers and national food service chains Potbelly and Shake Shack.

Following criticism, administration officials tightened regulations to channel more funds to smaller companies, and the average loan size fell to approximately $ 107,000 from nearly double that of mid-April. About $ 132 billion of funds are still available, and President Trump signed legislation Saturday that extends the application deadline from June 30 to August 8.

Nationwide, health care companies and firms that fall within the broad rubric of professional and technical services, ranging from law firms to landscape architects, received the largest amount of funds with nearly 13% of total US dollars. APP each.

Construction and manufacturing were next, followed by food and hospitality services, then retail, each holding around 8% of PPP dollars. However, food services and retail accounted for more than 10 million jobs lost in March and April, more than a third of total losses, far more than all other major sectors except health and social services.

Data released Monday shows that California companies received most of the nation’s funding: 13%, roughly proportional to the state share of 12% of the national population.

But there are disparities in how loans have been distributed. The District of Columbia, North Dakota, and Massachusetts received the bulk of the program’s per capita loans, while West Virginia, New Mexico, and Mississippi received the lowest amount of loans per capita.

“While the loans are smaller and more digestible, it appears that they have not yet reached the most vulnerable industries and states,” said Beth Ann Bovino, chief economist at S&P Global Ratings, who has been closely following the program. “So the question is: Of those 51.1 million jobs that are reportedly supported by PPP, how many were at risk of being lost in the first place?”

The new data does not shed direct light on how well PPP funds were distributed to minority-owned companies, which have been particularly affected by the pandemic, according to research by UC Santa Cruz economist Robert Fairlie. The borrower’s information on race and gender was voluntary, and most applicants left that part blank.

However, in its latest summary report of PPP approvals through June 30, the SBA said that 27% of PPP funds went to low- and moderate-income census tracts, in line with the participation of the general population in those areas.

“It’s good to see that the data is finally published in the PPP program, but frustrating that it took so long to come out,” said Sarah Crozier, a spokeswoman for the Main Street Alliance, a small business advocacy group that has been pushing for more transparency.

Times staff writers Samantha Masunaga, Hugo Martín, Laurence Darmiento, Wendy Lee, and Phil Willon contributed to this report.