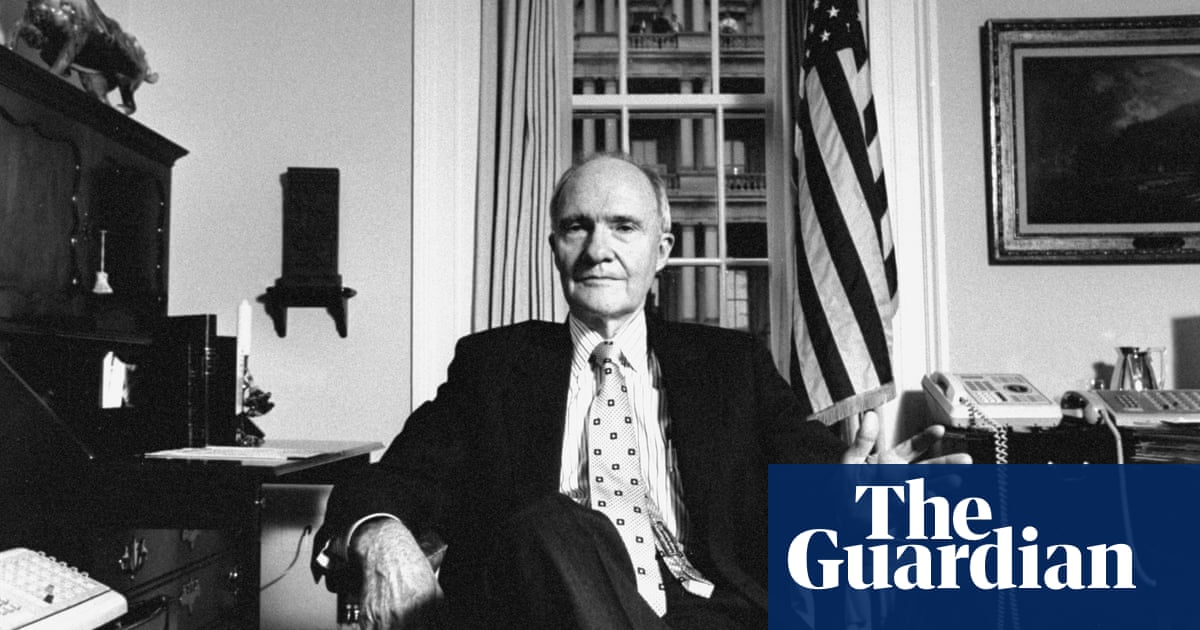

Despite his long and influential career in the conduct of US international affairs, Brent Scowcroft, who is 95 years old, did not draw much personal attention to himself. This low profile was surprising enough in 1975 when, as national security adviser in the Gerald Ford administration, he organized the evacuation of the US from Saigon, an event that marked the end of the Vietnam War.

More remarkably, he remained equally in the shadows when he was recalled to the same job 14 years later by the White House of George HW Bush. During that stint, he was caught on the hop by the fall of the Berlin Wall, by the imposition of the Soviet Union, and by Saddam Hussein’s attack on Kuwait.

However, he effectively replaced James Baker, the Secretary of State, as manager of US foreign policy during this crucial period of modern history. His immutable status with Bush Sr. was reinforced in 1998 when he was recognized as co-author of President A World Transformed’s memoir, in which Baker’s role in American policy was barely recognized.

Scowcroft’s entry to the highest levels of government came when he served as Richard Nixon’s military assistant in 1972, at the time of the President’s visit to China and the Soviet Union. Nixon National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger chose Scowcroft as his replacement when Alexander Haig moved to a senior military post early next year.

Kissinger was then heavily involved in the horrific toddler diplomacy that preceded the Vietnam peace talks, and also became secretary of state in September 1973, so Scowcroft took over much of the board of the National Security Council.

Among other responsibilities, he regularly provided the president with his daily introductory information and, in the wake of the Watergate crisis and Ford’s succession to the presidency, Scowcroft became Kissinger’s obvious successor when he left the security side in 1975. departed from his post.

Much of the new Security Adviser’s time was inevitably taken over by the humiliating end to America’s involvement in Vietnam, but he was also closely involved in the preparation of the Treaty of Salt II Restriction of Nuclear Weapons, eventually three years. later signed by President Jimmy Carter, but denied ratification by the U.S. Senate.

Scowcroft spent the Carter years (1977-81) as a private consultant, and continued to serve as vice president of Kissinger Associates (1982-89). Since the Republican right considered the arms reduction indicated under Salt II to be a sellout to the Soviet Union, it was also initially ignored by the Ronald Reagan administration.

But Reagan’s increasingly aggressive strategic policies, marked by the failure of a credible way of deploying the multi-warheaded MX rocket, brought Scowcroft back into the game in 1983 as chairman of a special presidential committee on strategic weapons.

The commission’s report did not please anyone, but it confirmed Scowcroft in its opinion that the arrival of the MIRV – the multiple independent warlords for re-entry cars installed on the MX and enabled it to Hitting 10 separate locations – was dangerously destabilizing. He thought it might undermine the 1972 anti-ballistic missile treaty. He strongly advocated the development of a single warhead replacement for the aging of the fleet of Minuteman missiles, first deployed in 1961, and Congress gave the project proper approval.

Scowcroft’s definitive duty for the Reagan administration was to serve on the Tower Commission investigating the Iran-Contra scandal, in which arms sold illegally to Tehran helped fund the US’s similar illegal attempt. to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Although National Security Adviser Admiral John Poindexter resigned and his assistant, Colonel Oliver North, was fired, Scowcroft argued that there was no need for drastic reform of the NSC. “It was not that the structure was defective,” he commented, “it was that the structure was not used.”

When Bush Sr. took over the White House in 1989, he brought Scowcroft back as head of the NSC. The administration’s direct occupations began with the president’s visit to China and then with his plan for a major reduction in superpowers in Europe – in response to Mikhail Gorbachev’s offer last month for 10,000 Soviet tanks and 500,000 troops. to withdraw.

The Chinese visit was notable for human rights abuses and, when the army brutally attacked Chinese students in Tiananmen Square after souring Gorbachev’s visit to Beijing, there was nothing more than a subdued reaction from the White House (although it later revealed that Scowcroft was secretly sent to China “to underscore American shock and concern”).

Meanwhile, Scowcroft felt that Gorbachev had been adequately banished in the domestic problems of perestroika that he could ignore for the time being and he seemed to extend this shining view to the rapid pressure for change in Eastern Europe.

The first indication of the new climate had come when Solidarity candidates sat on the board in the first free Polish elections. Despite this, Scowcroft seems to fully underestimate the significance of the parallel demonstrations in East Germany and the mass flight of its citizens to Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

When the demoralized and disorganized Erich Honecker regime finally emerged on November 9 to announce the permanent opening of the Berlin Wall, Scowcroft’s mistake of enlightenment was encapsulated in Bush Sr.’s bizarre remark that: ‘We are dealing with it a way we do not try to give everyone a hard time. ”

Despite this disgusting episode, Scowcroft believed that, although Gorbachev was loudly booed by the May Day threats on Red Square and Boris Yeltsin was elected President of the Russian Supreme Soviet, the general situation in the Soviet Union would be stable. to stay.

Then came the invasion of Iraq in Kuwait. Scowcroft acknowledged that he had dismissed the Iraqi rape as “part of a bluster policy” and this misjudgment provoked the crisis that took many of Bush Sr.’s Helsinki summit with Gorbachev. After Soviet support for retaliation was assured, Scowcroft and his staff were fully immersed in preparations for the Desert Storm campaign.

Then the unification of Germany and the aftermath of the Allied victory in Kuwait caused a euphoric state which hardly experienced the slow shrinkage of the Soviet empire, not only in the Baltic but in other non-Russian republics. Scowcroft’s focus was largely on the technologies of the Strategic Weapons Reduction Treaty, designed to cut Soviet and American nuclear weapons by half over the next 20 years.

Bush Sr. and Gorbachev signed Start I at the end of July 1991: three weeks later, furious hardliners in the Soviet military and KGB raged, rebelling against the Right-wing Americans’ view of arms reductions as sales to the enemy, on their attempt to coup. The White House had not received any indication of what was in it. Fortunately, it turned out to be a playful bungalow, but in the aftermath, the Soviet Union was formally disbanded in September and Gorbachev dismissed on December 25.

Days later, in his address to the United Nations, Bush Sr. canceled the Midgetman missile, halted further production of the B-2 bomber and the country’s most modern missile warhead and limited its advanced cruise missile arsenal. However, when Bush Sr.’s inadequate domestic policy cost him, Scowcroft’s days were numbered as well.

But there was one last shot in the closet. Shortly before Bush Sr. handed over to Bill Clinton, he met Yeltsin to sign the Treaty of Start II, which Scowcroft had done so much to commemorate. It specified the elimination of all MIRV land missile missiles within a decade. These accumulated moves to reduce core instability will likely be Scowcroft’s most enduring legacy.

Born in Ogden, Utah, he was the son of James Scowcroft, who ran a grocery business, and his wife, Lucille (nee Ballantyne). When he studied at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1947, he had conventional power care in mind. Commissioned as a pilot in the US Air Force, he was seriously injured a few months later in the landing of a defective aircraft. The accident had a devastating effect on him and for the next two decades he changed the course of his life several times.

Initially, he opted for personnel in the Air Force, but then enrolled at Columbia University to study international relations. Armed with his Columbia masters (1953), and already a specialist in Slavic languages, he returned to West Point to learn Russian history. In 1959 he became the Air Assistant to the U.S. Embassy in Belgrade, and two years later moved back to head the Department of Political Science at the U.S. Air Academy in Colorado.

After a brief stint at the Air Force headquarters in Washington and a further scholarship to the National War College, he received a doctorate from Columbia (1967) and eventually settled into the politico-military environment in which he could flourish.

His first move was to the Pentagon in 1968, when, at the age of 43, he joined his international security staff and worked his way up rapidly through a succession of ever-increasing positions. In 1971, after becoming a colonel, he was assigned to the White House to fill the very sensitive role of Nixon’s military assistant.

On the eve of Nixon’s historic visit to China, he was, of course, assigned to the U.S. delegation. Unexpectedly, he found himself the highest-ranking U.S. military officer to have arrived in Beijing since the 1949 revolution, and his work during the visit led to his promotion to brigadier general.

That and his fluent Russian made him a natural choice to organize the president’s visit to Moscow, where in 1972 the idea of mutual reduction of American and Soviet troops in Central Europe was first raised. From then on, the promotion of arms reduction became the overarching theme of Scowcroft.

When his full official involvement came to an end, he started his own international business advisory firm, the Scowcroft Group, in 1994. He then maintained the same discreet approach and moderate tone, his only public intervention coming in 2002 when President George W Bush was preparing for further war in Iraq.

In an advisory piece to the Wall Street Journal, Scowcroft advised attacking Saddam, citing too little evidence of references to al-Qaida as 9/11, and the risk that the US “could seriously endanger, if not destroy, the global counterterrorism campaign we have undertaken. ”But the son was not intimidated by what his father’s adviser had to say.

Its founding of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security in 2012 served as part of the Atlantic Council’s think tank to reaffirm its belief in the alliances that brought the Cold War to an end.

In 1951 he married Marian Horner; she died in 1995. He is survived by her daughter, Karen, and a granddaughter.

• Brent Scowcroft, International Security Adviser, born March 19, 1925; died 7 August 2020