Do you know those videos where people open (or even eat) WWII military rations? It is shocking to see how well preserved these “foods” can be after all those decades. In a way, Yuki Morono and his team of researchers from the Japan Earth and Sea Science and Technology Agency changed that experience by giving modern food to some ancient organisms. But his case involved removing ancient mud from the seabed and adding some food to see if there was anything alive there.

In fact, there were bacteria in the mud, which probably doesn’t sound surprising. But given the environment and age of these things, 100 million years old, it’s actually quite remarkable.

In deep

Deep life below the ground or below the seabed is not as well studied as the easily accessible surface world. Sampling has shown that seafloor mud in different parts of the ocean differs greatly in terms of the types and abundance of microbial life that are present. But in this case, the researchers took deep sediment samples in the middle of the South Pacific, where there is very little organic matter available for life to grow.

They grabbed sediment plugs up to about 70 meters below the sea floor. Very little sediment accumulates here, making the 70-meter-thick clay pile about 100 million years old. Mud at the bottom of lakes or swamps is often oxygen starved, as the respiration of bacteria that break down organic matter consumes everything. But food is so scarce here that oxygen, nitrate, and phosphate were present even in the deepest mud.

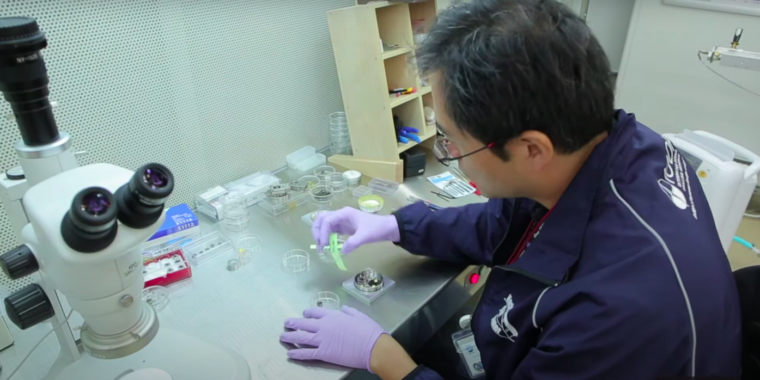

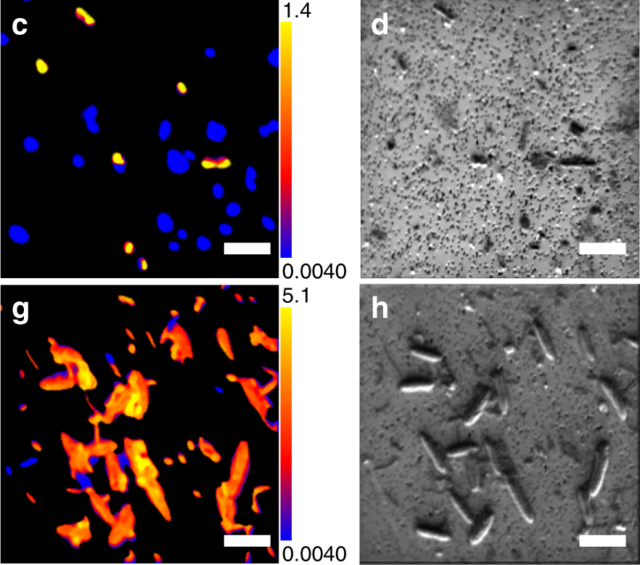

The researchers took these tiny plugs of sediment and injected substances that bacteria can use to grow, like sugar and ammonia. And indeed, the bacteria grew and engulfed them, even analyzing carbon and nitrogen isotopes in individual cells to verify that they had ingested those substances. The initial abundance of microbial cells was much lower than that found in more productive areas of the ocean, but they were present and viable.

The thing is, the researchers don’t think it’s just modern bacteria that have gotten into the mud. In fact, they shouldn’t be able to move absolutely in that mud The average space between particles in the clay must be considerably smaller than the size of a bacterium. The researchers conclude that the presence of microbes in the oldest sediments represents communities that are almost as old as the sediment itself.

The team scientists describe what they found in this video.

DNA analysis shows slightly different combinations of bacteria types present at different depths. However, almost all were aerobic bacteria that consumed oxygen. Some experiments did not add additional oxygen beyond what was already present in the mud, and the bacterial activity of the added food quickly used up all the oxygen. In those experiments, there was very little growth after the oxygen disappeared, suggesting that there are few anaerobic bacteria present. That contrasts with the food-rich seafloor sites where anaerobic bacteria dominate.

Extraordinary

This leads to an extraordinary statement: “Our results suggest that the widely distributed microbial communities in organically poor abyssal sediments consist primarily of aerobes that retain their metabolic potential in very low energy conditions for up to 101.5 [million years]. “

There are a couple of links in the chain where this could obviously go wrong. If the microbes have some mobility in the sediment, the ages disappear. But the argument against that, based on the diameter of the pore space and the existence of hard, waterproof layers, is reasonable. The other potential hazard is contamination, with bacteria entering the sediment sample from another location. But the team took several precautions here, including DNA samples taken at the time each sample was collected. If the unauthorized bacteria entered during sampling, they should appear in subsequent DNA samples, but not the initial one, and that did not happen.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t anything peculiar about the data. Cyanobacteria, photosynthetic microbes better known as “blue-green algae,” appear, which is certainly strange given the total lack of sunlight (and below) the seafloor. The specific genus of cyanobacteria is one that thrives in extreme conditions, at least. And its growth during the experiment also occurred in the absence of light, so the microbe may have some secrets to give up.

So if researchers are right about what they’ve found, it’s a testament to the fact that life is nothing but persistent. By slowing down to live within extremely limited means, these bacterial communities may have survived for a simply incredible period of time.

Nature Communications, 2020. DOI: 10.1038 / s41467-020-17330-1 (About DOIs).