By Yael Annemiek Engbers, University of Liverpool and Andrew Biggin, University of Liverpool.

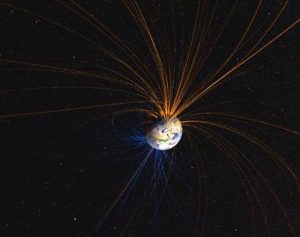

At the bottom of the Earth, liquid iron flows and generates the Earth's magnetic field, which protects our atmosphere and satellites against harmful radiation from the sun. This field changes over time and also behaves differently in different parts of the world. The field can even change polarity entirely, with the north and south magnetic poles shifting places. This is called reversal and it last happened 780,000 years ago.

Santa Elena, where the Earth's magnetic field behaves strangely. Image via Umomos / Shutterstock / The conversation.

Between South America and southern Africa, there is an enigmatic magnetic region called the South Atlantic Anomaly, where the field is much weaker than might be expected. Weak and unstable fields are believed to precede magnetic reversals, which is why some have argued that this feature may be evidence that we are dealing with one.

Now our new study, published on June 12, 2020, in the procedures of the National Academy of SciencesHe has discovered how long the field has been operating in the South Atlantic, and sheds light on whether it is something to worry about.

Weak magnetic fields make us more prone to magnetic storms that have the potential to destroy electronic infrastructure, including power grids. The magnetic field of the South Atlantic Anomaly is already so weak that it can adversely affect satellites and their technology when they fly by. The strange region is believed to be related to a patch of magnetic field that points in a different direction than the rest at the top of the planet's liquid outer core at a depth of 1,795 miles (2,889 km) within Earth.

The geomagnetic field on the Earth's surface with the South Atlantic Anomaly outlined in black and Santa Elena marked with a star. Colors range from weak fields (blue) to strong fields (yellow). Image via Richard K. Bono / The conversation.

This "reverse flow patch" itself has grown over the past 250 years. But we don't know if it is simply a unique product of the chaotic movements of the outer core fluid or, rather, the latest in a series of anomalies within this particular region over long periods of time.

If it is a non-recurring feature, then its current location is not significant; It could happen anywhere, maybe randomly. But if this is the case, the question of whether its increasing size and depth could usher in a new reversal remains.

However, if it is the latest in a series of features that repeat over millions of years, then a reversal would be less likely. But it would require a specific explanation of what was causing the magnetic field to act strangely at this particular location.

Volcanic rocks

To find out, we traveled to Santa Helena, an island in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. This island, where Napoleon was exiled and finally died in 1821, is made of volcanic rocks. These originate from two separate volcanoes and erupted between eight million and 11.5 million years ago.

Lead author Yael Engbers is drilling a core in Saint Helena. Image via Andy Biggin / The conversation.

When volcanic rocks cool, the small grains of iron oxide in them become magnetized, and thus keep the direction and strength of Earth's magnetic field at that time and place. We collected some of those rocks and took them back to our laboratory in Liverpool, where we conducted experiments to discover what the magnetic field looked like at the time of the eruption.

Our results showed us that the field at Santa Elena had very different directions throughout the eruption time, showing us that the field in this region was much less stable than elsewhere. Therefore, it challenges the idea that abnormality has only existed for a few centuries. Instead, the entire region has probably been unstable on a time scale of millions of years. This implies that the current situation is not as rare as some scientists had assumed, making it less likely to represent the beginning of a reversal.

A window into the Earth.

So what could explain the strange magnetic region? The liquid outer core that generates it moves (by convection) at speeds so high that changes can occur on very short human time scales. The outer core interacts with a layer called the mantle on top, which moves much more slowly. That means the mantle is unlikely to have changed much in the past ten million years.

Internal structure of the Earth. Image via Wikipedia.

From the seismic waves that pass through the Earth, we have an idea of the structure of the mantle. Beneath Africa there is a great feature in the lower mantle where the waves move more slowly through the Earth, which means that there is very likely to be an unusually warm region of the lower mantle. This possibly causes a different interaction with the outer core at that specific location, which could explain the strange behavior of the magnetic field in the South Atlantic.

Another aspect of Earth's interior is the inner core, which is a solid ball the size of Pluto below the outer core. This solid feature is growing slowly, but not at the same rate everywhere. There is a possibility that it is growing faster on one side, causing a flow within the outer core that is reaching the outer limit with the rocky mantle just below the Atlantic hemisphere. This may be causing irregular behavior of the magnetic field in the long time scales that we find in Santa Elena.

Although there are still many questions about the exact cause of irregular behavior in the South Atlantic, this study shows us that it has existed for millions of years and is likely the result of geophysical interactions in the mysterious interior of Earth.

Yael Annemiek Engbers, Ph.D. candidate, University of Liverpool and Andrew Biggin, professor of paleomagnetism, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Will Earth face a magnetic pole reversal soon? Hear from the authors of a new study about a strange anomaly that could be a clue.

![]()

.