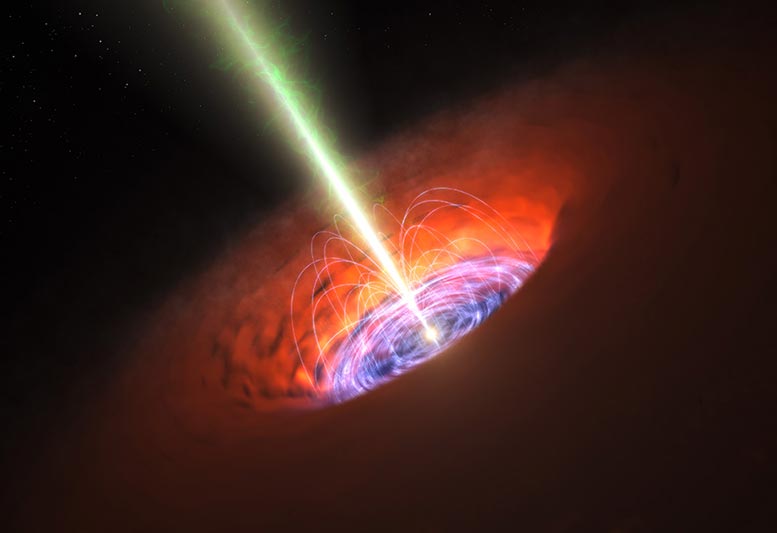

Artist’s impression of an internal accretion flow and jet from a supermassive black hole when actively feeding, for example, on a recently ripped star. Image: ESO / L. Calçada

A 50-year theory that started as speculation about how an alien civilization could use a dungeon Generating power has been experimentally verified for the first time in a Glasgow research laboratory.

In 1969, British physicist Roger Penrose suggested that energy could be generated by lowering an object into the black hole ergosphere, the outer layer of the black hole’s event horizon, where an object would have to move faster than the speed of light to stay. still.

Penrose predicted that the object would acquire negative energy in this unusual area of space. By releasing the object and dividing it in two so that one half falls into the black hole while the other recovers, the recoil action would measure a loss of negative energy; indeed, the recovered half would gain energy drawn from the rotation of the black hole. However, the scale of the engineering challenge that the process would require is so great that Penrose suggested that only a highly advanced, perhaps bizarre, civilization would equal the task.

Two years later, another physicist named Yakov Zel’dovich suggested that the theory could be tested with a more practical and terrestrial experiment. He proposed that the “ twisted ” light waves hitting the surface of a rotating metal cylinder rotating at the correct speed would end up reflecting off additional energy drawn from the cylinder’s rotation thanks to a peculiarity of the rotational Doppler effect.

But Zel’dovich’s idea has only remained in the realm of theory since 1971 because, for the experiment to work, his proposed metal cylinder would need to rotate at least a billion times per second, another insurmountable challenge for current limits. of human engineering.

Now, researchers at the Glasgow UniversityThe School of Physics and Astronomy has finally found a way to experimentally demonstrate the effect Penrose and Zel’dovich proposed by twisting sound instead of light, a much lower frequency source and therefore much more practical for demonstrate in the laboratory.

In a new article published on June 22, 2020, in Physics of natureThe team describes how they built a system that uses a small ring of loudspeakers to create a turn in sound waves analogous to the turn in light waves proposed by Zel’dovich.

Credit: University of Glasgow.

Those twisted sound waves were directed at a spinning sound absorber made of a foam disk. A set of microphones behind the disc picked up the sound from the speakers as it passed through the disc, constantly increasing the speed of its spin.

What the team sought to hear to find out that Penrose and Zel’dovich’s theories were correct was a distinctive change in the frequency and amplitude of the sound waves as they traveled through the disc, caused by that peculiarity of the Doppler effect.

Marion Cromb, a doctoral student at the University’s Faculty of Physics and Astronomy, is the lead author of the article. Marion said: “The linear version of the doppler effect is familiar to most people, since the phenomenon that occurs when the tone of an ambulance siren seems to increase as it gets closer to the listener, but falls when it moves away. It seems to increase because sound waves reach the listener more frequently as the ambulance approaches, and less frequently as it passes.

“The rotational Doppler effect is similar, but the effect is limited to a circular space. Twisted sound waves change their pitch when measured from the point of view of the rotating surface. If the surface spins fast enough, the frequency of sound can do something very strange: It can go from a positive to a negative frequency, and in doing so, steal some energy from the surface’s rotation. “

As the speed of the spinning disk increases during the researchers’ experiment, the pitch of the sound from the speakers decreases until it becomes too low to hear. The tone then rises again until it reaches its previous, but louder, tone, with amplitude up to 30% greater than the original sound coming from the speakers.

Marion added: “What we heard during our experiment was extraordinary. What happens is that the frequency of the sound waves shifts Doppler to zero as the spin speed increases. When the sound starts again, it is because the waves have moved from a positive frequency to a negative frequency. Those negative frequency waves are able to take part of the energy of the rotating foam disk, becoming stronger in the process, as proposed by Zel’dovich in 1971. “

Professor Daniele Faccio, also from the Faculty of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Glasgow, is co-author of the article. Professor Faccio added: “We are delighted to have been able to experimentally verify some extremely strange physics half a century after the theory was first proposed. It is strange to think that we have been able to confirm a theory of half a century ago with cosmic origins here in our laboratory in western Scotland, but we believe that it will open up many new avenues of scientific exploration. We are eager to see how we can investigate the effect on different sources, such as electromagnetic waves in the near future. “

Reference: “Amplification of waves of a rotating body” by Marion Cromb, Graham M. Gibson, Ermes Toninelli, Miles J. Padgett, Ewan M. Wright and Daniele Faccio, June 22, 2020, Physics of nature.

DOI: 10.1038 / s41567-020-0944-3

The research team’s article, titled ‘Amplification of Rotatable Body Waves,’ is published in Physics of nature. The research was supported by funds from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program.