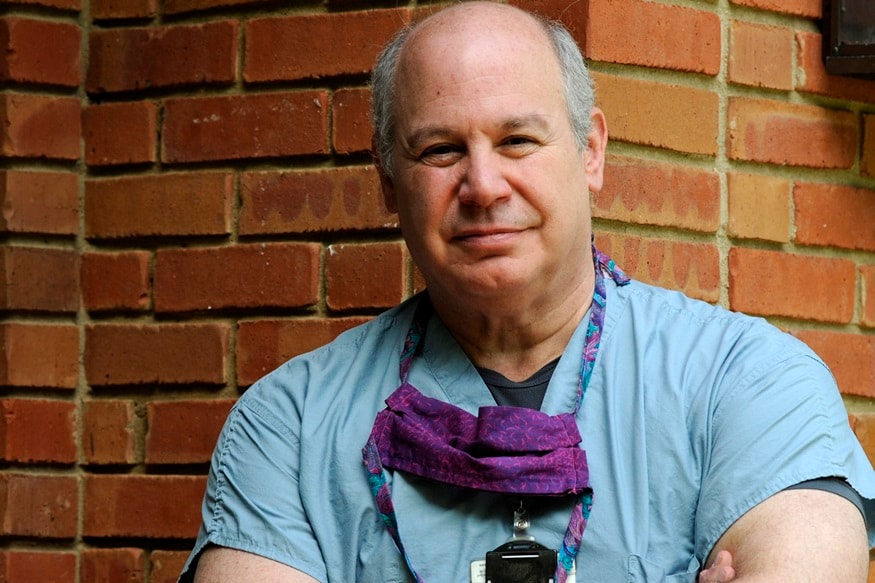

Dr. Michael Saag, who survived COVID-19 and is now treating patients with the disease, poses for a portrait at his home in Mountain Brook, Alabama on Friday, July 10, 2020. (AP Photo / Jay Reeves)

Confirmed cases of COVID-19 have increased an average of more than 1,500 per day in the past week in Alabama, bringing the total to more than 62,100 since the pandemic began in March.

- Associated Press

- Last update: July 18, 2020 11:12 PM IST

Dr. Michael Saag spends much of his time treating patients who are fighting for their lives and working with colleagues who are overwhelmed and exhausted by the relentless battle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

But he enters a different world when he walks out the door of his Alabama clinic: one in which many do not wear masks, stay away from others, or even seem to be aware of the intense fight being waged against a virus that has cost hundreds of thousands. of lives across the country and made many, including the doctor, seriously ill.

Disconnection is devastating.

“It is a mix of emotions, from anger to demoralization, bewilderment and frustration,” said Saag.

Confirmed cases of COVID-19 have increased an average of more than 1,500 per day in the past week in Alabama, bringing the total to more than 62,100 since the pandemic began in March. At least 1,230 people have died and health authorities say less than 15% of the state’s intensive care beds are available to new patients. Some hospitals are completely out of the room.

It is not just an Alabama problem. About 250 miles (400 kilometers) from Birmingham, Dr. Chad Dowell warns that his hospital in Little Indianola, Mississippi, is filling up and others too, making it difficult to locate beds for the sickest patients, even when the People debate on social networks if the pandemic is real.

Inside the University of Alabama Hospital in Birmingham, doctors and nurses in protective gear rush from one emergency to the next. They are struggling to comfort heartbroken visitors who are forced to say goodbye to their dying long-distance family members by cell phone, Saag said, as they deal with the stress of whether they will be infected next.

The sharp increase in confirmed virus cases in Alabama has coincided with the reopening of restaurants, bars, theaters, gyms, sports leagues, and churches that closed when the virus first attacked. Although most have opened to decreased capacity and with established restrictions, many customers have not followed the recommended precautions.

In the Birmingham subway, where Saag lives, it has been common to see less than half of people inside stores wearing masks. The doctor said he was recently particularly discouraged after passing a restaurant on his way home from work to pick up a take-out sushi order. There were up to 60 people inside, he said.

“Me and one other person were the only two people wearing masks. And everyone else, not only did they not wear masks, but they congregated together,” he said. “And they look at me like I’m some kind of outcast wearing a mask.”

In response, Governor Kay Ivey this week ordered all Alabama residents age 6 and older to wear masks when in public and within 6 feet of someone who is not related. Against a pandemic that has become increasingly political, the movement received both praise and a potentially life-saving move and harsh criticism from those who called it an unnecessary affront to freedom.

Saag said he hopes the order helps, but it all depends on compliance. Ivey herself said the rule will be difficult to enforce, and some police and sheriff’s offices have said they won’t even try.

During the initial outbreak, doctors and nurses were hailed as heroes in the fight against COVID-19. Some say they now feel more like cannon fodder in a war that has become increasingly divisive.

“People continue to view the virus as a political scheme or conspiracy theory. People continue to ignore the recommended guidelines on how to help delay the spread of the virus. People continue to complain about wearing a mask. We have to do better as a community, ”Dowell, the Mississippi physician, wrote in a Facebook message posted by the South Sunflower County Hospital.

For Saag, the fight is personal. In early March, he and his adult son both contracted the virus after a trip to Manhattan when the epidemic was at its peak. First came a cough, followed by a fever, a headache, a body ache, and what Saag called “confused thinking,” or an inability to concentrate.

“In the morning I would feel good, I thought it was over. And then every night, it came back like it just started again, ”he said. “The hardest part of the night was that feeling of shortness of breath and not knowing if it will get worse.”

For eight stifling nights, Saag was unsure if she would survive without a fan. It never came to that. Now she is fully recovered and feels closer than ever to the people she treats.

“When I talk to a patient and say, ‘Hey, I had it too,’ it’s like we’re connected in a way that I’ve really, honestly never felt with patients before, and I’ve been doing this for 40 years,” Saag said. .

Outside of the exam room, Saag has participated in press conferences and conducted media interviews to promote basic public health practices, but he knows that many people are simply not listening.

He said it is disheartening to see widespread disregard for security measures and he worries about Alabama’s future at a time when the virus poses a threat more than ever.

“I’m just thinking, ‘Oh my gosh. We’re going to be in trouble very soon, ‘”Saag said.

.