[ad_1]

Millions of Indians who have been out of work for weeks face hunger as the country struggles with the coronavirus outbreak.

The most vulnerable are daily wage earners, contract workers and migrant workers who have been without jobs or earnings since the country closed on March 25.

It comes when the World Food Program analysis suggests that an additional 130 million people worldwide “may be on the brink of starvation by the end of 2020” as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

David Beasley, executive director of the World Food Program, warned the UN Security Council that the world is “on the brink of a hunger pandemic” that could lead to “multiple famines of biblical proportions.”

Hundreds of men, women and their children have been waiting in the hot sun for a lovely meal in Gurgaon, outside the Indian national capital, Delhi.

Mujibur, a worker, is there to pick up a hot meal for his wife Mariam, who gave birth to a baby during the shutdown.

It is past noon and this is the first meal you will eat until dinner time.

She said: “It is a big problem for me, there is no food, no money and I have a baby, I am very worried about him. Whatever they give us is everything I eat all day.”

The biggest problem everyone faces is the availability of food and rations.

They have been out of work for weeks and most have exhausted their savings.

The closure has stripped them of everything, including their dignity.

Hundreds here live in clusters of one-bedroom houses, some even in tin sheds and shacks made of plastic sheeting and bamboo.

They are workers, masons, drivers, maids, cleaners, guards, and vegetable vendors who care for thousands of high-rise homes and apartments that dot this cyber city.

Lalla Bai, a daily wage worker, left her two children in the village to come and earn a living.

Desperate to return home, she said, “We are angry at the government, they are starving us. They are neither killing us nor allowing us to live. We are caught in the middle. I cannot go back to my children.” “

She insists that we enter her bamboo and plastic sheeting hut.

It’s stifling since the temperature is already touching 40C (104F) and this is just the beginning of the long summer.

Social distancing is a privilege that these people cannot afford.

:: Listen to the daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Jamshed lives with his wife and four children in a room with a ceiling and three sides of tin foil.

A daily worker, he arrived in the city three months ago and regrets his decision.

“Food is the biggest problem and since there is no job I have no money to buy anything,” he said.

Tanuja, a 36-year-old cleaner, collapsed when she said, “This disease has crushed us. I have no job, no food, no money to pay rent. My children are in town and I have to send them money.” . What will I do.”

Common laundry areas coupled with unsanitary living conditions and lack of personal protection means that the pandemic would plague this group.

The informal sector of daily wage earners, contract workers and migrant workers constitutes almost 81% of the country’s active population.

The government has established thousands of relief camps where free food and shelter are provided to the trapped poor and migrants.

But with the overwhelming numbers, not everyone can be contacted all the time.

Two days after the closing, a restaurant owner, Vishal Anand, was detained in his car by people asking for food.

He said that “they were not beggars, but skilled and unskilled workers and they just wanted food.”

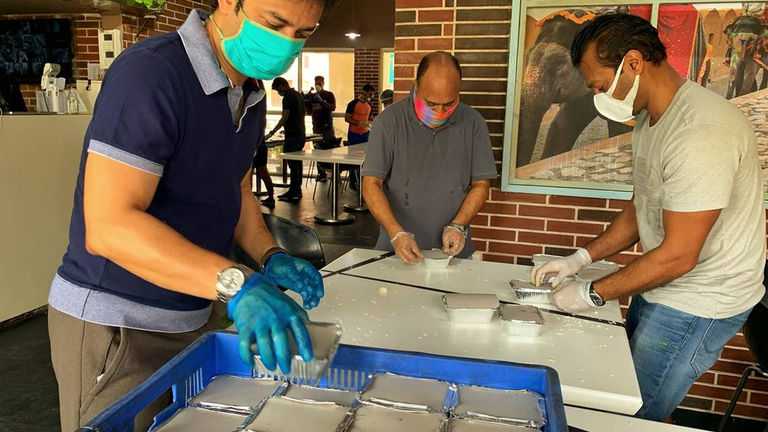

Anand gathered his finances and with a group of his friends and volunteers started a kitchen preparing thousands of hot meals.

With limited resources, the idea was to provide food to the most vulnerable for just a few days until the administration stepped up.

But with the overwhelming number of hungry people, they couldn’t stop.

Mr. Anand told Sky News: “As citizens, the first thing I believe in is that we need to help other citizens. The most important thing we have to do is secure them with basic food and rations for the next 90 days. I really don’t we do it “I don’t know when the closure will end and when they will return to their respective jobs.”

With the help of some charities, donations and the administration, he and his friends are making life a little easier for the thousands of forgotten poor.

It is an uncertain future for this vast invisible majority, many desperate to return home to their families.

Geeta, from Panna in Madhya Pradesh, said: “Our children are starving at home and we here have nothing here. We want to return. Our children will die there and we will die here.”