[ad_1]

In 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa set an ambitious goal of $ 100 billion in new investment over the next five years to jump-start an economy stunted by a decade of looting and mismanagement by Jacob Zuma. According to the latest UN data, after three years, South Africa is woefully short of this target.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), foreign direct investment flows to South Africa in 2020 nearly halved to $ 2.5 billion from $ 4.6 billion in 2019, representing a decrease in the 15% of around $ 5.4 billion in 2018.

The cumulative total over the three years comes to $ 12.5 billion, which may seem like a really large number in rand terms. But President Cyril Ramaphosa in 2018 set an investment goal of $ 100 billion over five years, and at an investment conference in Sandton in October of that year, various industry titans made no less than $ 55 billion in pledges. investment.

More than half the way! Talk about action, talk about kept promises! From the Karoo to the Limpopo, it was as if money fell from the sky. Investors were in love with South Africa, which knelt down and carried suitcases full of cash.

Talk about smoke and mirrors.

UNCTAD monitors these sorts of things, and while its data may not be accurate, it publishes its global FDI findings annually and they are a pretty good indicator of broader trends. And, by almost any measure, South Africa is lagging behind.

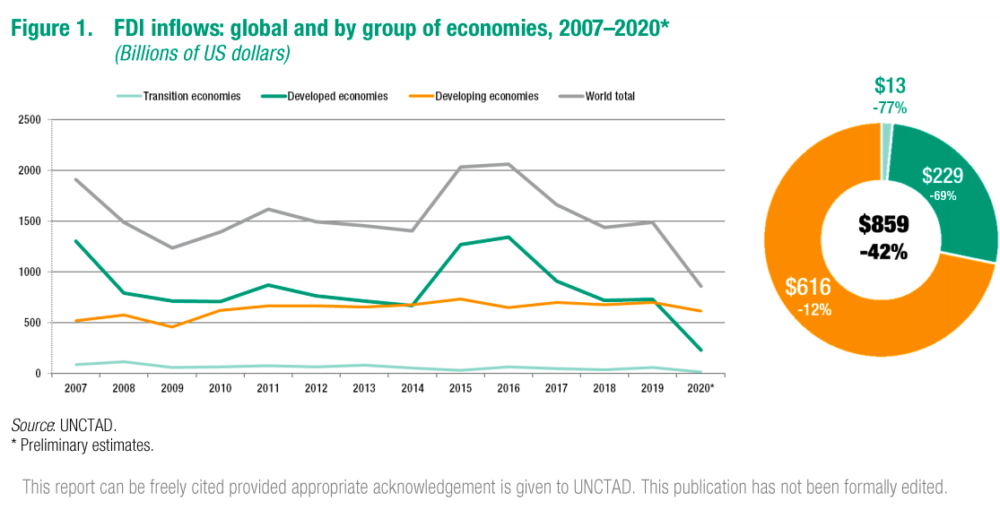

So in 2020, almost everywhere, FDI flows were reeling due to the pandemic and lockdowns to reduce its spread. Globally, the amount of FDI in 2020 fell 42% to $ 859 billion from $ 1.5 trillion in 2019. At 69%, the decline was most pronounced in developed economies such as Europe and the US.

By contrast, in developing economies, the largest peer group in South Africa, the decline was much less pronounced, 12%. Sub-Saharan Africa saw an 11% drop in FDI in 2020, which, all things considered (the collapse of oil markets, the global economic downturn, increased investor risk aversion) was not a success train. Then look at South Africa’s 46% drop and the image that immediately comes to mind is an economy derailed.

UNCTAD also notes that: “The share of developing economies in global FDI (in 2020) reached 72%, the highest share on record.” A lot of that has to do with China, which, of course, completely broke the trend by posting a modest 4% increase in FDI inflows last year. The broader point here is that existing FDI flows are being funneled into developing economies and yet South Africa can only attract a trickle, while a tsunami passes.

Pretoria is clearly missing the boat.

So what is going on here? In terms of investment flows, much of the $ 55 billion pledged at Sandton in the heady days of late 2018 was already in the country or in the pipeline, to be spent over an extended period. South Africa also has domestic sources of investment capital, but a low savings rate means that it is never enough, which is why foreign capital is so essential.

There are also foreign portfolio flows to bond and JSE markets, but unlike FDI, this is capital that can come and go with relative ease. FDI is coveted (the platinum standard, so to speak) because it is capital that is spent on physical assets such as building factories or mines or laboratories or shops, anchoring itself in the economy.

This also translates into employment, which is why each FDI advertisement tends to tout the number of jobs it creates or intends to create on paper.

And South Africa is really bad at attracting FDI: the facts speak for themselves and the reasons are as clear as a bottle of cane. Eskom is at the top of the list. Factories and mines, you know, the things you expect to find in a modern industrial economy, require reliable power supplies. Yet from DMRE to NERSA, new self-generation and renewable projects remain stillborn, crushed under mountains of bureaucracy.

The impression is that such projects will only get the go-ahead when ANC cadres can benefit, which may be unfair, but recent history suggests that this is a plausible explanation for inertia. Also on the mining front, the dysfunctional AMD cannot even produce a working cadastre, a publicly available overview of the geological data and mining rights it has granted. Not surprisingly, South Africa accounts for less than 1% of the world’s mining exploration spending. And without exploration, no new mines will be built.

This list could go on, of course. Planned investments in new brewing capacity have been destroyed by the clumsy ban policy. South Africa’s high rates of violent crime and social unrest dramatically increase security costs, and thus the cost of doing business. Tax rates are very high with a very low rate of return.

The state is lacking in capacity: the first impression a foreign investor has of South Africa may well be shaped by relations with Home Affairs, which by most opinions is a chaotic mess. Crucial infrastructure is falling into a state of disrepair, which is what happens when cities like Johannesburg are run by cadres looking at their own bottom line.

Policy target positions continue to shift, and rising levels of public debt will continue to undermine the value of the rand, adding to layers of uncertainty. It also increases borrowing costs for the private sector, as it must go to lenders in the context of a sovereign credit rating on junk. Productivity levels are generally low and confidence levels are in the gutter.

Attracting FDI does not mean that a country has to bow down and kiss the ring of capital in some Trumpian fantasy destroying all its regulations and labor laws. In an era of ESG (environmental, social and governance concerns) and growing corporate disclosure, few companies want to be associated with things like child labor or a mining project that poisons hundreds of elephants.

But they want a return on their capital and a stable investment environment. South Africa is not offering it at the moment. “$ 12.5 billion in three years!” This is not an inspirational slogan for political rallies. But the fact is that it is a fact. DM /BM

![]()