[ad_1]

File Photo: A general view of Clifton Lackay queuing and buying alcohol at Blue Downs Mall on the 66th day of the national lockdown on June 1, 2020 in Cape Town, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Roger Sedres)

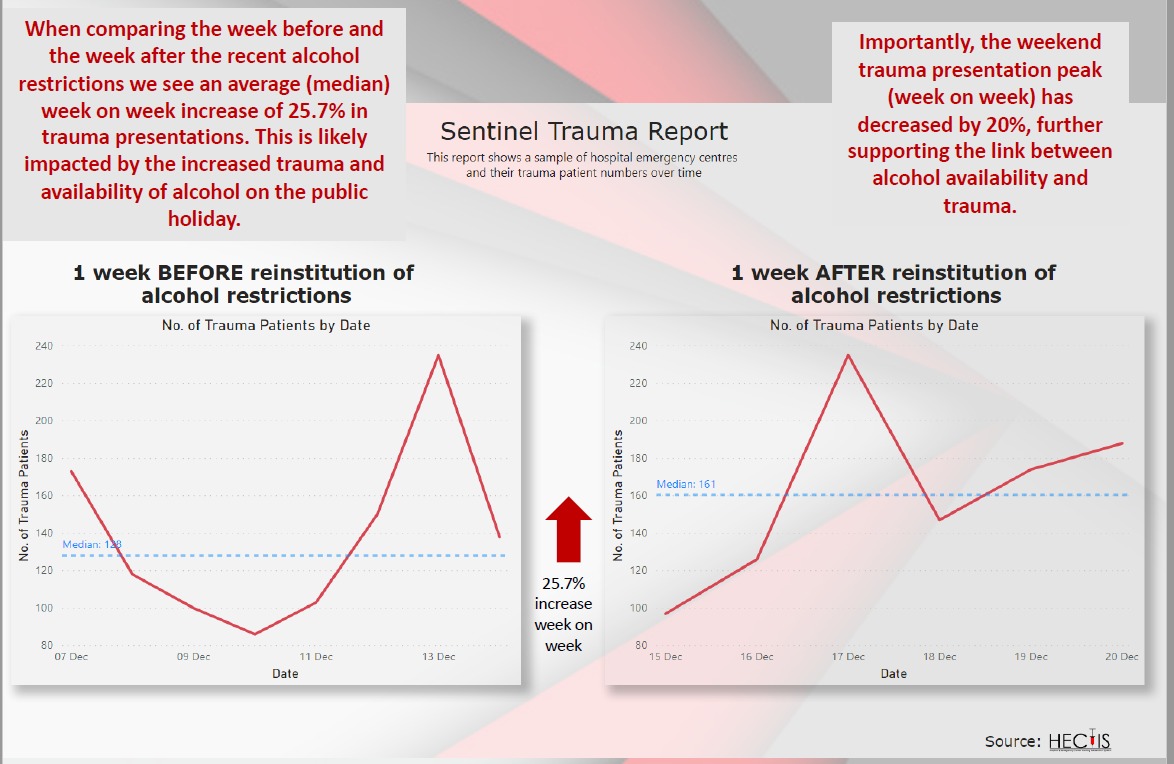

In a recent digicom presented by Alan Winde, the Western Cape Prime Minister made it clear that trauma presentations were increasing rapidly – by 26% across the five hospitals in the Western Cape Trauma Surveillance Sentinel System, even after the restrictions on the number of meetings and on the sale of alcohol. and a stricter curfew from December 16.

Christmas comes once a year. Yet each year, like this repeated refrain, doctors and nurses prepare for the aftermath of Christmas as our festivities drag on well into the New Year. Victims of stab lacerations, gunshot wounds, traffic collisions, and gender-based violence, all present in the hospital, each requiring evaluation, management, very often admission and sometimes ventilation in the ICU.

This year is no different.

And yet it is also completely different. We are on the sidelines witnessing the clash of two epidemics as our hospitals fall to the brink to cope with sick Covid-19 patients and those with alcohol-related conditions.

Both conditions can be prevented.

Most will have heard and read about the tumult in Western Cape hospitals and many will have experienced it first hand. Western Cape Covid-19 case numbers followed increases on the Garden Route and Eastern Cape in early December. Patients have waited in line for beds, oxygen, nurses; ambulances have gone from one hospital to another after the diversion announcements; staff are sick with Covid-19, others are in quarantine, many are exhausted; oxygen capacity is on red alert; and politicians have expressed the seriousness of the situation.

Requests for medical and nursing volunteers have been sent out to help get through the next few days, and some will answer the call. But there won’t be enough.

We are not prepared for what awaits us during the New Year.

We were prepared for the first wave of Covid-19, with the heavy-handed lockdown aimed at ensuring that hospital capacity was available. Was. The merits of the lockdown and its disastrous effects on the broader economy, and the inaccuracies of the model projections are still important to discuss and learn from, but at this point, we must identify the key drivers of the increase in admissions and act accordingly. . .

Now, not after the crisis.

We present two specific interventions for the government’s consideration, both based on strong evidence, to implement immediately to cover the period through January 3, 2021. We have seen that when there is the will, the government has been able to act promptly.

We present two specific interventions for the government’s consideration, both based on strong evidence, to implement immediately to cover the period through January 3, 2021. We have seen that when there is the will, the government has been able to act promptly.

I should do it again.

Interventions needed to curb alcohol-related admissions

Alcohol use, and especially heavy alcohol use, is causally related to trauma admissions. This relationship is indisputable to scientists around the world. The availability, price and affordability of alcohol, as well as marketing practices, have increasingly been shown to have an impact on alcohol use and associated harms.

In a recent digicom presented by Alan Winde, the Western Cape Prime Minister made it clear that trauma presentations were increasing rapidly – by 26% across the five hospitals in the Western Cape Trauma Surveillance Sentinel System, even after the restrictions on the number of meetings and the sale of alcohol. , and a tighter curfew from December 16 (read the Western Cape statement here and watch it on FB here).

In a recent digicom presented by Alan Winde, the Western Cape Prime Minister made it clear that trauma presentations were increasing rapidly – by 26% across the five hospitals in the Western Cape Trauma Surveillance Sentinel System, even after the restrictions on the number of meetings and the sale of alcohol. , and a tighter curfew from December 16 (read the Western Cape statement here and watch it on FB here).

More than 30% of patients presenting with trauma require admission.

By taking steps to reduce trauma presentations in these five and other hospitals, it should be possible to reduce the demand for beds in general wards, operating room time, ICU beds, ventilators, and hospital staff and materials. .

In a previous Daily Maverick article (Charting a healthier path for alcohol in South Africa, now and in the future, 7/27/20), one of the authors (Charles Parry) proposed a 10-point plan to better manage alcohol. alcohol. related harm and to reduce pressure on hospital staff and other resources when the second ban on the sale of alcohol is lifted.

Currently, only one of those measures is in effect: restricting the sale of liquor for off-site consumption between 10 a.m. M. And 6 p.m. M., Monday through Thursday. This should remain in place, as reducing sales hours and days even further can have the unintended consequence of crowding stores and leading to panic purchases.

Many of the other evidence-based approaches to reducing alcohol-related harm require major policy changes and consultation with the community, but we must quickly implement more interventions. Additional considerations, which can be quickly enacted, would be to suspend all alcohol sales at the facility through January 3, 2021, and ban special price promotions on alcohol at this time. The latter will send a clear message to the industry and the public that the marketing of cheap alcohol during a pandemic is unethical.

Recommendation 1: Maintain current restrictions on the sale of off-the-shelf liquors and suspend all sales and consumption of alcohol on the premises, for example, in bars, restaurants and taverns; and prohibit promotions of discounted alcoholic beverages in all media and liquor sales establishments

Interventions to stop Covid-19 transmissions

SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes Covid-19) is transmitted by droplets from the nose, mouth, or eyes that are passed from one person to another. It is increasingly recognized that it is also spread by air.

Regardless of the transmission route, we increase our risk of acquiring Covid-19 when we gather in tight and crowded spaces. The definition of close contact, according to the National Institute of Communicable Diseases, is being within 1 meter of someone with confirmed Covid-19 (symptomatic or not) for 15 minutes or more, without a mask. It’s not a long time, especially when you’re having fun, and masks only provide protection when used in combination with other measures.

Add alcohol to that mix and unsurprisingly, we’ll start to lose our inhibitions. We forget to wash our hands, get close to our family member or friend, take off our uncomfortable mask and stay longer than expected.

Our current regulations limit indoor meetings to 100 people and less than 50% of the capacity in any establishment. This remains reasonable in the long run, and the responsibility for managing it appropriately rests with restaurants, businesses and places of worship. We understand the need to balance economic imperatives with health and safety measures. Restaurants are in their peak season and reducing capacity further will undermine their sustainability and profit margins. Therefore, additional restrictions should first focus on alcohol restrictions as outlined above, but consideration should be given to further reducing the number of people who are allowed to gather indoors to 50. Until 3 May January 2021.

Meanwhile, gathering outdoors in small groups is much safer for everyone, limited to regular household members and only close friends.

Recommendation 2: Further reduce indoor meetings to 50 people and keep less than 50% capacity indoors

Both recommendations are intended as short-term interventions and attempt to balance the needs of the economy and the wishes of the public with the urgent need to reduce hospital presentations.

We see that they are powerful and potentially regressive tools, impacting the poor more than the rich. We look at the many ascending social determinants of alcohol use and abuse in our country. We looked at evidence-based interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm outlined by the World Health Organization and ourselves, including restricting the density of outlets on and off the premises; price increases and taxes, including the minimum unit price; and restricting the advertising of alcoholic beverages. All of these remain central to the broader public health discussions around alcohol that we must have as a country once the worst is over.

At this time, we must act and urge the government to consider our recommendations. We are committed to collecting and collating data on trauma and admissions by the end of January to provide an indication of the usefulness of such actions and to build the evidence base so that we will not find ourselves in this situation again in December 2021. DM / MC

Nandi Siegfried is Chief Specialist Scientist, Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council; Honorary Associate Professor, Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town. Charles Parry is Director of the Research Unit on Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs of the Medical Research Council of South Africa; Extraordinary Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Stellenbosch University.

Acknowledgments: We thank Dr. Virginia Zweigenthal for her comments, the Western Cape Department of Health for sharing the trauma statistics with us, and Dr. Douglas Parry for his help with the data.

![]()