[ad_1]

Research says Covid-19 disease is associated with an abnormal immune reaction called a cytokine storm.

->

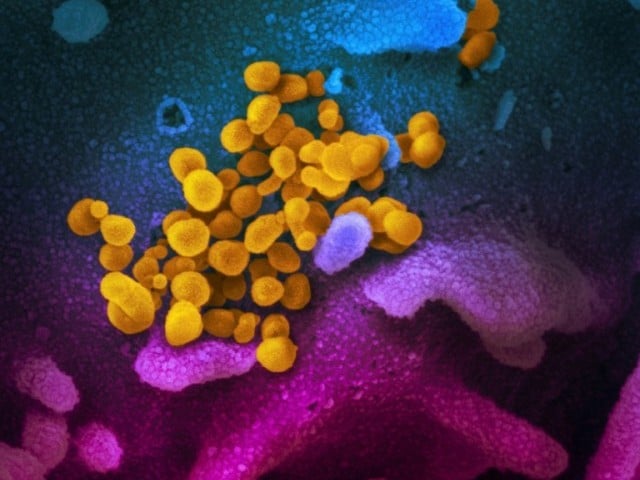

An image taken with a scanning electron microscope shows SARS-CoV-2 (yellow), also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes Covid-19. PHOTO: AFP

WASHINGTON: After spending nearly three weeks in an intensive care unit undergoing Covid-19 treatment, Broadway doctors and television actor Nick Cordero were forced to amputate his right leg.

The 41-year-old blood clot had been hampered by a clot – another dangerous complication of the disease that has emerged in front-line reports from China, Europe, and the United States.

No doubt, so-called “thrombotic events” occur for a variety of reasons among intensive care patients, but the rates among Covid-19 patients are much higher than would be expected.

“I have been 40 years old in my ICU who have clots in his fingers that seem to lose the finger, but there is no other reason to lose the finger than the virus,” Shari Brosnahan, a critical care physician at NYU Langone said AFP.

France to reveal plans on how Covid-19 blockade will be reduced

One of these patients suffers from lack of blood flow in both feet and both hands, and she predicts that an amputation may be necessary, or the blood vessels can become so damaged that a limb could fall off on its own.

Blood clots are not only dangerous to our extremities, but can reach the lungs, heart, or brain, where they can cause lethal pulmonary embolisms, heart attacks, and strokes.

A recent article from the Netherlands in the journal Thrombosis Research found that 31 percent of 184 patients suffered thrombotic complications, a number the researchers rated “remarkably high”, even if extreme consequences like amputation are rare.

Why is this happening?

Behnood Bikdeli, a physician at New York Presbyterian Hospital, brought together an international consortium of experts to study the topic. Their findings were published in the Journal of The American College of Cardiology.

A medical team delivers a COVID-19 patient to an intensive care unit in Stamford, Connecticut. PHOTO: AFP

The experts found that the risks were so great that Covid-19 patients “may need to receive anticoagulants, preventively, prophylactically,” even before imaging tests are ordered, Bikdeli said.

What exactly is causing it? The reasons are not fully understood, but he offered several possible explanations.

People with severe forms of Covid-19 often have underlying medical conditions like heart or lung disease, which in turn are linked to higher coagulation rates.

Then being in intensive care makes a person more likely to develop a clot because he stays still for a long time. This is why, for example, people are encouraged to stretch and move on long-haul flights.

It is now also clear that Covid-19 disease is associated with an abnormal immune reaction called “cytokine storm,” and some research has indicated that this is also related to higher coagulation rates.

There could also be something about the virus itself that is causing clotting, which has some precedent in other viral illnesses.

An article in The Lancet magazine last week showed that the virus can infect the inner cell layer of organs and blood vessels, called the endothelium. This, in theory, could interfere with the coagulation process.

Microclots

According to Brosnahan, although diluents like heparin are effective in some patients, they do not work for all patients because the clots are sometimes too small.

“There are too many microclots,” he said. “We are not sure exactly where they are.”

In fact, autopsies have shown that some people’s lungs are filled with hundreds of microclots.

The arrival of a new mystery, however, helps solve a slightly older one.

Cecilia Mirant-Borde, an intensive care doctor at a veteran’s military hospital in Manhattan, said AFP The microclot-filled lungs helped explain why ventilators malfunction for patients with low blood oxygen levels.

Previously in the pandemic, doctors treated these patients according to protocols developed for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sometimes known as “wet lung.”

WHO chief says pandemic is far from over, concerned about children

But in some cases, “it is not because the lungs are full of water,” but that microcoagulation is blocking circulation and the blood is leaving the lungs with less oxygen than it should.

Just under five months have passed since the virus emerged in Wuhan, China, and researchers are learning more about its impact every day.

“While we reacted in surprise, we shouldn’t be as surprised as we were. Viruses tend to do weird things,” Brosnahan said.

While the dizzying array of complications may seem daunting, “there may be one or a couple of unifying mechanisms that describe how this damage occurs,” he said.

“It is possible that everything is the same and that there is the same solution.”

[ad_2]