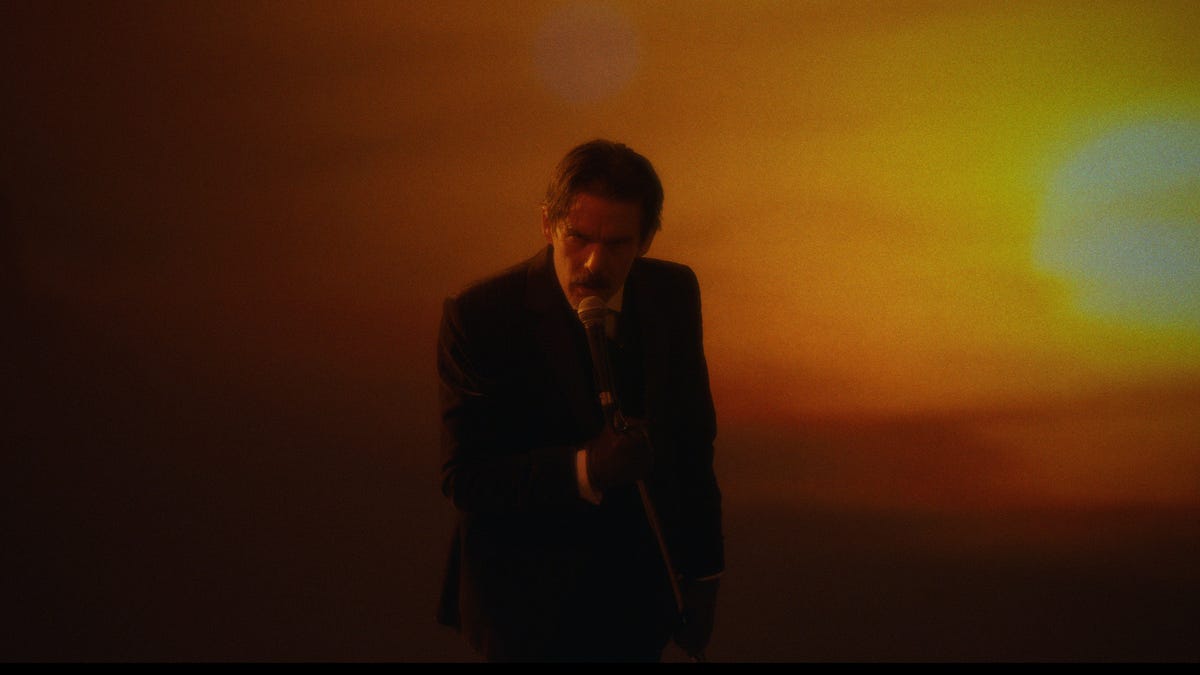

In a touching scene that comes after the end of Michael Almereyda’s postmodern quasi-biopsy Tesla, the inventor Nikola Tesla (Ethan Hawke) rushes to a tennis court where his former financier, the tycoon JP Morgan (Donnie Keshawarz), is playing a game with his daughters. Speak through a chainlink gate, Tesla makes impossible promises: He develops a machine that can photograph thoughts and plans to make superweapons that will make war a thing of the past. Morgan is no longer interested, so Tesla goes off to do a karaoke release of Tears For Fears ‘Everybody Wants To Rule T’he World ”while recording solar rays behind him is projected.

Similar moments of early poignancy are scattered throughout the film, meaning more than a little self-identification. After all, if there is one industrial futurist that artists can claim as one of their own, it is the eccentric publicity dog Tesla, who has spent his personal fortune and ‘millions’ of investors on unattainable projects that he claimed for the betterment of man. Almereyda, who is at his best as an irreverent director of ideas, is smart enough to regard this last part of the legend with skepticism. To him, Tesla’s boonies are the work of a lone mind trying to prove his vision of the universe. The only relevant questions are the same ones we ask of visionary artists, whose life work is rarely practical or complete.

This is an analogy to that Tesla draws more than once – pointing out, for example, that the $ 150,000 Morgan lost on Tesla’s experiments with wireless power was an amount that the Wall Street titan was more than willing to spend on individual paintings for his art collection. As he did in some of his most memorable works (including his turn-of-the-millennium update of Hamlet and his biopic of Stanley Milgram Experiment), Almereyda sheds light on its own budget constraints: The film is full of anachronisms meant for anyone who takes biopics literally, and sees their less avant-garde parts distressingly as cheap re-actions of tv, no favors done by indie filmmaker Sean Price Williams’ common love for diffusion filters and underexposed faces.

What these anti-aesthetic qualities seem to question is whether a more expensive-looking film would be better than less fake. These are some intriguing questions – because we to do know what a more expensive version of Tesla would look, seeing as the past decade has produced several slickly styled scientific biopics, including The theory of everything, The Current War, en Radioactive. The latter of these even has moments that, on a conceptual level, would not seem out of place in Almereyda’s film. But the fact that these films are similar is an unfortunate truth about Tesla: that it is, in some respects, conventional.

What’s more, the conventions it shares with other films are some of the hottest, including awkward exposition dialogues and scenes of science that show off surprising extras; the latter suffer under the fact that Almereyda has exactly zero interest in the kind of showmanship that made Tesla a national celebrity. Putting this game in anonymous empty local-historical-society interiors does not qualify very much as deconstruction. Of course, the film is nothing if not hyper-aware of its phonology. Some of the ideas – say, the image of Thomas Edison (a beautiful Kyle Maclachlan) as a cultural icon who is always in his 50s, even if he was in his early 30s – make interesting remarks about how we present history. Others fall flat; When a group heir disrupts a party to the sound of dated electro-pop, the result is both obvious and trying.

Almereyda, however, understands something lost on some similarities minded projects: thas theatrical effects of distancing – something in Tesla include breaks from fourth walls, told by Google supported by Morgan’s daughter, Anne (Eve Hewson) – works best when combined with the demonstrably opposite values of believable performance. For the most part, these performances are delightfully unshowy. (Edison of Maclachlan, for one, is head and shoulders above the irritating painting of Benedict Cumberbatch of the Wizard Of Menlo Park in The Current War.) Hawke, who previously worked with Almereyda Hamlet and another adaptation of Shakespeare, Cymbeline, is so soft-spoken that he even underscores Tesla’s accent.

Far from the flamboyant figure of fantasy and popular myth, this version of the inventor is completely interior. TeslaThe most beautiful sequences are those that briefly and wordlessly evoke a sense of isolation and quixotic pursuit: the germophobic Tesla erases his silverware as he sits down for a meal for a black-and-white photo of an empty hotel room; Tesla looks out over the Colorado landscape on a projection screen while a windmill blows on its extensively parted hair; the image of the Tesla Experimental Station at Colorado Springs as a fragile-looking model. While these images strongly contrast with the film’s self-conscious, sometimes artless collage, they convey a level of sympathy that is lacking in slimmer, more consistent films.

.