At the Tate Modern museum in London, they reopened just after the coronavirus lockon, to discover that the installation – thought to have been bold when it first opened last fall in the museum’s enormous entrance – now seems positive clairvoyant.

It’s a statement about slavery by American artist Kara Walker. While explaining in an accompanying video, “[This] is an allegory of the Black Atlantic Ocean, and indeed all world waters that catastrophically connect Africa with America, Europe, and economic prosperity. England was the benefactor of the slave trade and its products. And so, you have this kind of institution that spans many hundreds of years, and that everyone is involved in. “

Everyone involved, including the people who run this entire museum, named for the Tate family who made their fortunes in the sugar business, a company founded on slave labor. Great works of art, great irony, notes correspondent Mark Phillips.

CBS News

And if the statue looks a bit familiar, it’s because it’s modeled on one of London’s most famous monuments: the impressive memorial to Queen Victoria that has sat in front of Buckingham Palace for more than a century. It has classic images to commemorate a monarch who ruled under the power of the British Empire, while Walker’s monument at the museum (titled “Fons Americanus”) the dark side of imperial history shows – the horrors of the forced transportation of African slaves to work in the British colonies in North America and the Caribbean.

The work was well commissioned before the assassination of George Floyd and the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, which also took hold here, with large demonstrations on the streets of London and other cities.

“It feels very timely,” said Tate curator Achim Borchardt-Hume, who feels the artwork is even more relevant now. “Now we are in a moment where, both in the UK and in the States, the conversation revolved around what is happening with monuments in the public realm everywhere.”

Part of the conversation in England, as in the US, includes controversial symbols of the past. Many people killed a statue of slave trader Edward Colston in the port city of Bristol. Se dan dumped it in the same port of which his ships once sailed to retrieve cargo from slaves in Africa.

CBS News

“Personally, I did not shed tears before taking down Colston in Bristol,” Keith McClelland told Phillips. “I mean, the man was a monster.”

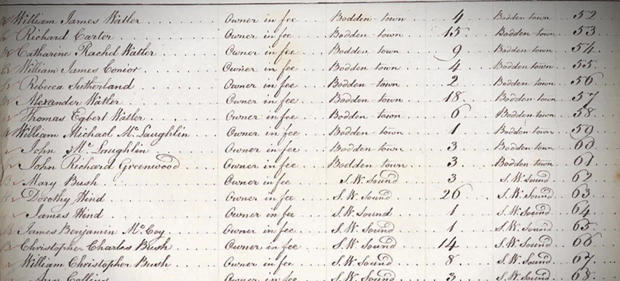

McClelland needs to know about monsters with slave trade; he and a team of historians at the prestigious University College London spent years conducting a database of all slave owners in Britain who received compensation when slavery was abolished here in the 1830s.

Method records from the time show that the payout was enormous, the equivalent of about $ 3 billion now, given not to the slaves but to the slave-owners.

“The information is all, it’s all public, “said McClelland of the Legacies of British Slave database. Who got the money? Some were rich pillars of society, like George Hibbert, then paid around £ 40,000 – about $ 6 million in today’s money.

“This is a man who did not need the spare change by appearance, “said Phillips.

CBS News

Hibbert owned thousands of slaves; some property much less, such as Ann Huie, who received nearly £ 49 (now worth about $ 7,000) in compensation for her two enslaved people.

“The government will not repay the loan to the Bank of England until 2015,” said Black Kehinde scientist and author. For him, the fact that the British government borrows money to compensate the slave owners – and only recently repaid the loan – means that, in a cruel turn, the generation of immigrants moving to Britain from the Caribbean ended up rack.

“I, my grandmother, and all the descendants of the enslaves have actually paid reparations to slave owners for slavery, through our taxes,” Andrews said. “It’s insane, right?”

“Have you paid back for your own slavery? Asked Phillips.

“Yes, we have literally paid for the freedom of our ancestors, “Andrews said.

The wealth of many modern British businesses and families can be traced back to original investments made with those payments. Greene King’s pub chain is just one example; it is now embarrassing to invest funds to combat racism.

The same goes for Lloyds of London, one of the largest insurance markets in the world, which made huge profits from the slave trade.

Andrews said: “Lloyds of London is so deeply rooted in slavery, it’s where it started. The business model was to insure slave ships. The idea that they could simply propose a diversity system and give some money to charity is, honestly, insulting. . “

Philips asked: “Is this a point where the next stage of change is happening?”

“Well, I find it interesting that it took the killing of someone 3,000 miles away for Britain to begin to recognize its racism in many different forms,” Andrews said.

It does not happen only in Britain. The death of a man under the knee of an American cop has forced several former colonial powers to confront dark sides of their history. In Paris, the statue of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, author of the “Black Code” for the treatment of slaves in French colonies, was painted red.

In Belgium, statues of King Leopold II, notorious for his brutal rule over 10 million Africans in the Congo, suffered a similar fate.

The murder of George Floyd, Andrews said, “is actually just the straw that broke the camel’s back. In America, the protests are not just about police brutality or about murder. They are about everything else. And here it is. the same way.We have the same problems of economic disadvantage, education disadvantage, unemployment, COVID 19. And so, we see – and have historically seen – racism is not an American problem; it is a world problem.And now, we have that global conversation. “

In Bristol, where the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston had stood, a local artist erected a statue of one of the Protestants.

CBS News

The city took it down the next day. The conversation still has a way to go.

For more info:

Story produced by Mikaela Bufano. Editor: Brian Robbins.

.