Scientists have seen thousands of worlds in other solar systems, so many that exoplanets have become a dime a dozen. But in our neighborhood, three-quarters of the planets have at least one Moon, and no such object in other systems has been confidently discovered so far, such worlds are too small and too far away.

Now, a new document points to six exoplanets where the oscillations in your data can be caused by exomoons. But that does not necessarily guarantee the presence of such moons, and at this time there is no way for scientists to determine the actual details of the situation. Those are great challenges for any research to overcome.

“We can say that these six new systems are completely consistent with exomoons,” said lead author Chris Fox, a doctoral candidate at Western University in Canada, he said in a statement. “But we don’t have the technology to confirm them by imagining them directly. That will have to wait for more progress.”

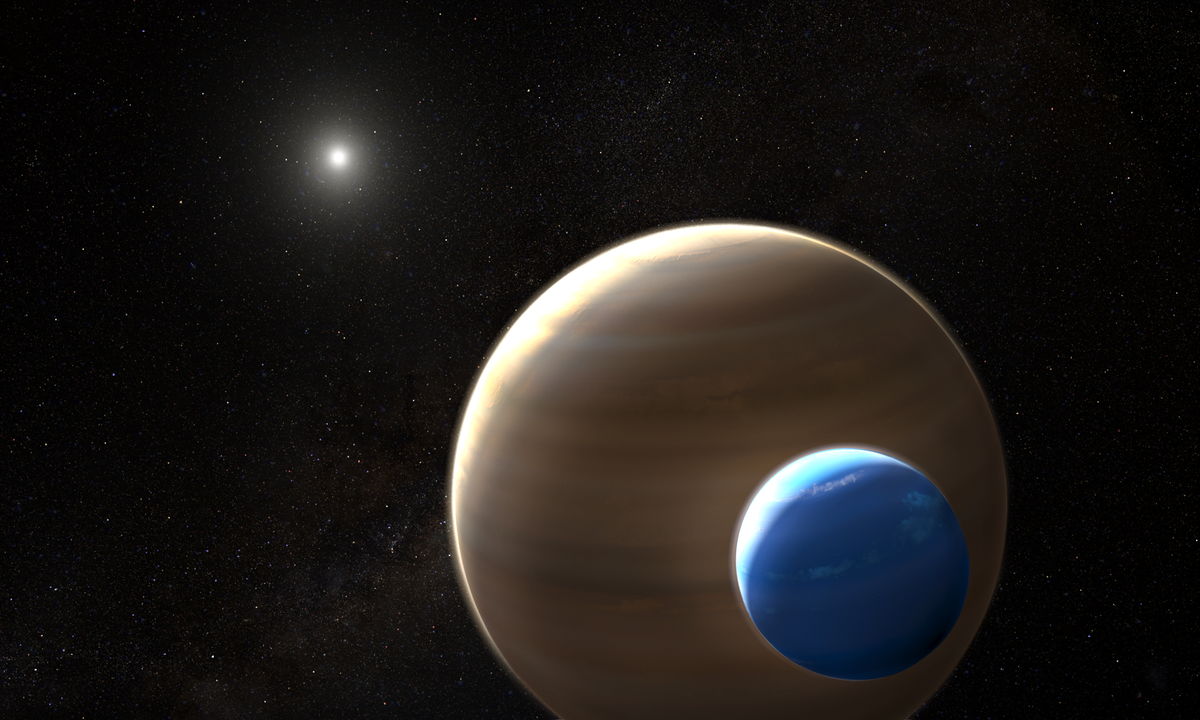

Related: First exomoon found? Neptune-sized world possibly seen in orbit alien planet

But exomoons are tantalizing enough that scientists don’t want to just wait, Alex Teachey, a doctorate candidate at Columbia University who specializes in exomoons, told Space.com by email.

“We believe that finding moons could produce a variety of ideas about the formation and evolution of other planetary systems, help contextualize ours. Solar system (how common or rare we are) and are potentially attractive places to search for life in other parts of the galaxy. “

That said, the focus in the new study may not be the best way to search for exomoons, Teachey said. The researchers carefully studied the data collected by the now retired NASA. Kepler space telescope, which has identified many of the more than 4,000 exoplanets Scientists know to date.

Kepler’s main tactic for studying exoplanets was to look at individual stars and measure their brightness. If a planet and its star are properly aligned with the telescope, the star will dim briefly as the planet crosses its disk, or transits, through the telescope’s view. The larger the planet, the more the star dims during a transit.

But sometimes, the glitter data on a traffic seems a little messy. There’s a wiggle here or there, and it doesn’t go away. That’s when scientists begin to wonder if they might be seeing something else, not just a planet.

And it’s that kind of transit that the scientists from the new research decided to study. The research is described in a work presented which has not yet undergone a peer review and was released on the preprint server arXiv.org on June 23.

The researchers observed eight stars with transits that seemed rhythmically a little muted. Instead of a perfect orbiting metronome, transit occasionally came a little earlier or later than scientists would have predicted. And for six of those stars, scientists found in the new research, the cause of that syncopation could be a moon.

The problem is that the cause could be many other things as well, particularly another planet in the system that doesn’t cross between the star and our telescopes, so scientists haven’t identified it yet.

“One question we have to deal with is, how plausible is a moon in a given system, particularly a massive moon? “Teachey said.” We don’t really have a good answer for that right now. On the other hand, we know that a planet without transit is very plausible. That doesn’t mean that is the explanation, but it is quite conceivable. “

In particular, Teachey said, he would like to see more signs of an exomoon’s influence on traffic, particularly a moon itself. transiting the star. The systems the researchers studied are too small for that kind of signal to appear, and Teachey said scientists still have a lot of analysis to do on the Kepler data that would show such signs.

And in those transits, he said, scientists could rule out more alternatives, increasing the strength of an exomoon hypothesis, rather than simply not ruling out an exomoon as the cause of the peculiarities of a transit.

“There are a lot of rocks to turn around before we start to feel like a moon is the best explanation,” said Teachey.

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us On twitter @Spacedotcom and in Facebook.