Once a person becomes ill with coronavirus there is no guarantee that they will not contract it again, new research suggests.

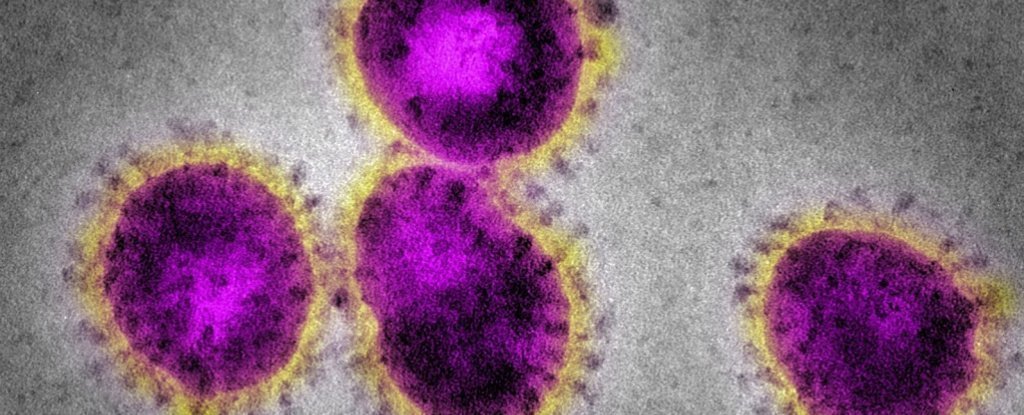

While SARS-Cavi-2 is the coronavirus that is the focus of the current world, there are many others we have known for decades who are not only known to infect humans, but are very seasonal.

Researchers have studied four species of this seasonal coronavirus over the last 35 years, and found that around one year after the first round, the infection reappeared.

While it doesn’t necessarily say anything about the current global epidemic, it’s not a good sign for the hope of long-term immunity in a population.

Analyzing 513 serum samples collected from the 1980s from 10 healthy men living in Amsterdam, the researchers noted several spikes of antibodies to the coronavirus.

Each of these spikes was interpreted as a redirection, and four seasonal coronaviruses were studied – including HCOV-NL63, HCOV-229E, HCOV-OC43, and HCOV-HQ1 – three to 17 per patient per team. Were infected.

Some rare recombinations were shown early in the six months after the initial infection, but more often, they returned about a year later, “showing that the immune system is only for a short life.”

To date, there have been some confirmed cases of COVID-19 resuscitation, but many have faced controversy, as it is not too early to say how long immunity for SARS-COVID-2 can last.

Paying attention to other coronaviruses is our best key, and unfortunately, this 35-year study suggests that immunity to many coronavirus infections is not only temporary, it is short-lived. What’s more, the authors say that rearrangement may be a common feature of all human coronaviruses.

Studies have limited that antibody levels only act as a proxy for coronavirus infection – we cannot say for sure that each optic in antibodies was precisely a re-enzyme.

Research was also done on a small sample of participants, so a large group study is needed.

That said, he has some assumptions that are not made by other research.

“Our serological study is unique in that it avoids the sample bias of previous epidemiological studies based on symptom-based testing protocols,” the authors of the new study said.

Instead, patients were tested regularly, several times a year for several decades, when they were healthy. This is important because many coronavirus infections can remain asymptomatic, which means we will ignore many refractions.

Recent research, particularly on SARS-Covy-2, suggests that within the first 2 months after infection, especially after mild cases (which most people get) certain antibody levels begin to decline.

The new study found a similar timeline.

Blood samples, collected every 3 months before 1989 and every 6 months (on an unexplained six-year gap in the data), show that most coronavirus infections in Amsterdam occurred in the winter.

The authors write, “In our study, the four seasonal coronavirus infections are lowest in June, July, August and September,” the authors write. This feature can be shared in the post-epidemic era. ”

This is similar to research on other human coronaviruses, which show that infection rates slow down in the summer.

The Northern Hemisphere is now in a definite collapse, with very worrying consequences if new findings apply to the current global epidemic.

Does SARS-CoV-2 follow the same trend that other coronaviruses have yet to see. But if we are to be as careful as possible, we should not assume that long-term immunity is one thing, because in the end, reliance on vaccinations and natural immunity we can only get from this virus.

Achieving a long-lasting immune response to the vaccine can be difficult. It may be that we receive regular updates, as we do with seasonal flu.

The study was published in Nature medicine.

.