Some microbes below the seabed have hit us: they can survive with little sustenance for more than 100 million years.

These microorganisms live more than 18,000 feet below the surface of the ocean, in an area so deep that it is called the subsoil, below the sea floor.

The area, part of the Earth’s system of spinning ocean currents, doesn’t have much food to feed next to nothing. It is relatively low in plant nutrients, but contains abundant oxygen in the deepest parts of the subsoil.

It is not a place where most of life would thrive, although microbes under the seabed were known to be present at Gyre sites in the South Pacific. Fortunately for microbes, their population was not limited by the availability of nitrogen and iron or other dissolved inorganic nutrients necessary for the growth of living things.

Life under the sea

Until now, there hasn’t been much evidence of how these hungry microbes work and their survival status in a food-scarce environment, the study said. This is because before a cell can grow, divide into more cells, or maintain the energy necessary to complete basic metabolic functions, it must consume and use carbon.

The sediment was deposited 13 million to 101.5 million years ago and contains small amounts of carbon and other organic materials.

Then, in a laboratory, the researchers fed these multi-million dollar samples with carbon and nitrogen substrates, materials an organism feeds on, to assess whether the cells were able to feed and divide into more cells.

Most of the nearly 7,000 ancient cells analyzed easily consumed the carbon and nitrogen foods within 68 days of the incubation experiments.

They also quickly divided and increased their total numbers more than 10,000 times.

After 101.5 million years in food shortage conditions, dormant microbes retained their abilities to stay alive, eat, and divide. These microbes dominate the microbial communities housed in the sediment in the abyss of the ocean, according to the study.

“The microbes are trapped almost entirely in the sediment, surrounded by grains, they are not allowed to move,” and they stayed there for millions of years, Morono said.

“Furthermore, its nutrients are very limited, almost in the ‘fasting’ state,” Morono added in an email. “Therefore, it is surprising and biologically challenging that a large fraction of microbes can be revived from a very long burial or entrapment time under extremely low nutrient / energy conditions.”

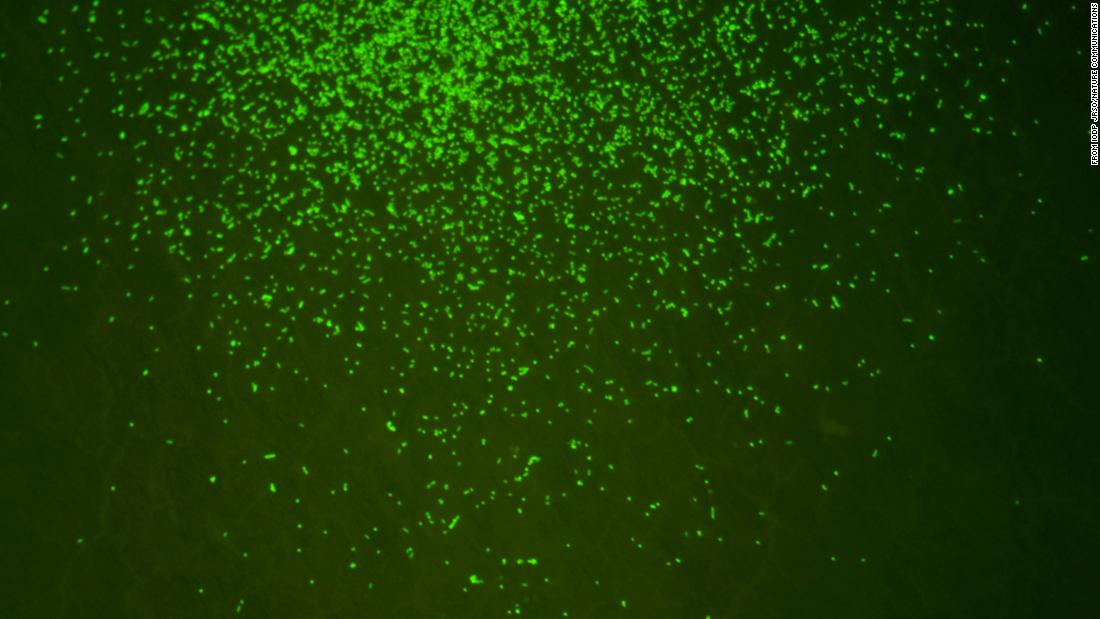

The microbes only represented less than 0.01% of the sediment samples, so the techniques used allowed the microbes imperceptible to the human eye to be visible and recognizable by humans, Morono said.

The study is “of global importance, but it is difficult to extrapolate to the other (ocean sediment), because the sediments are complex and vary from site to site,” said Yohey Suzuki, an associate professor in the department of earth and planetary sciences at The University of Tokyo, which was not involved in the study.

The authors also discovered various types of bacteria with high tolerance to extreme environmental conditions.

How they survived

The revived microbes were trapped in the subsoil sediment for up to 100 million years without food, and researchers have not yet discovered how the microbes could have survived such an extreme shortage.

In addition to determining how the microbes could survive for millions of years, the authors also “hope to see the limits of the subsoil,” Morono said.

“We now know that there is no age limit (for organisms), but there should be the end of the biosphere somewhere underground,” he said. “We want to see the extent of habitable space on our Earth and learn in detail the condition that limits life.”

.