Microsoft on Tuesday fixed 120 vulnerabilities, two notable for being under active attack and a third for repairing an earlier patch for a security flaw that could allow attackers to gain a backdoor that persists even after updating a machine used to be.

Rarities for zero days get their name because a affected developer has zero days to release a patch before the security flaw is under attack. Zero-day explosions can be of the most effective, as they are not normally detected by antivirus, burglary prevention systems and other security protections. These types of attacks typically pose a threat to top-tier agents because of the work and skill required to identify the unknown vulnerability and develop reliable exploitation. Add to that the hassle: the exploits have to bypass defenses that developers have spent a lot of resources on implementing.

The hacker’s dream: bypass code signing controls

The first zero-day is present in all supported versions of Windows, including Windows 10 and Server 2019, making security professionals consider two of the world’s most secure operating systems. CVE-2020-1464 is what Microsoft calls a Windows Authenticode Signature Spoofing vulnerability. Hackers who exploit it can defeat their malware on targeted systems by bypassing a malware defense that uses digital signatures to certify that software is reliable.

Authenticode is Microsoft’s own coding technology to ensure that an app as a driver comes from a known and trusted source and is not approached by anyone. Because they customize the OS kernel, drivers can only be installed on Windows 10 and Server 2019 if they carry one of these cryptographic signatures. On earlier versions of Windows, digital signatures still play an important role in helping AV and other protections to detect malicious goods.

The typical route for attackers to circumvent this protection is to sign their malware with a valid certificate stolen from a legitimate provider. The investigation into Stuxnet, the worm that many believe targeted Iran’s nuclear program a decade ago, was one of the first times researchers discovered the tactic used.

Since then, however, researchers have found that the practice dates back to at least 2003 and is much more widespread than previously thought. Stolen certificates remain a regular occurrence with one of the more recent incidents involving a certificate that was stolen in 2018 from Nfinity Games to sign malware that infected several Massively Multiplayer Online game makers earlier this year.

CVE-2020-1464 made it possible for hackers to reach the same bypass without the hassle of stealing a valid certificate or worrying about it being revoked. The host of Windows affected versions suggests that the vulnerability has been around for years. Microsoft did not provide details about the cause of the vulnerability, how it is being used, by whom, or who the targets are.

Microsoft typically credits investigators who report bug fixes, but Microsoft’s update page for this month’s update does not mention CVE-2020-1464. A Microsoft representative said the discovery was made internally through research conducted at Microsoft.

IE: As old as it is unsafe

The other zero-day attack can install malware of the attacker’s choice if targets view malicious content with Internet Explorer, an old browser with an outdated code base that is vulnerable to all kinds of exploits.

According to security company Sophos, CVE-2020-1380 comes from a use-to-free class of bug that allows attackers to load malicious code into a memory location that is freed once its previous contents are no longer in use. The vulnerability is contained in the just-in-time compiler of IE’s JavaScript engine.

One way in which attackers can exploit the error is by planting booby-trapped code on a website where the target visitor is. Another method is to embed a malicious ActiveX control embedded in an application such as a Microsoft Office document using the IE rendering engine. Despite the vulnerability, Windows will show that the ActiveX control is “safe for initialization.”

There is no doubt that the in-the-wild explosions are alarming to the people as well as organizations that have been attacked. But overall, CVE-2020-1380 is less about the internet as a whole because of the small threat to users. With the advent of advanced protections in Chrome, Firefox, and Edge, IE has gone from a browser with almost monopolistic use to one with less than 6% market share. Anyone who still uses it should give it up for something with better defenses.

A “late” break with a removable fix

The third fix released on Tuesday is CVE-2020-1337. The number, 1337, which hackers often use to spell “leet”, as in “elite”, is one notable feature. The more important difference is that it is a patch for CVE-2020-1048, an update that Microsoft released in May.

The May patch could fix a privilege escalation vulnerability in Windows Print Spooler, a service that manages the printing process, including finding printer drivers and loading and placing print jobs.

Recently, the error made it possible for an attacker with the ability to execute code with low privilege to fix a backdoor on vulnerable computers. The attacker could return at any time to gain access to powerful System Rights. The vulnerability resulted in a print pooler that could allow an attacker to write arbitrary data to any file on a computer with system privileges. This made it possible to fix a maliciously crafted DLL and get it executed by a process that runs with system privileges.

A detailed technical description of this error is provided in this post by researchers Yarden Shafir & Alex Ionescu. They note that the print spooler has not received much attention from researchers despite it being some of the oldest code still running in Windows.

Less than two weeks after Microsoft released the patch, a researcher with the handle math1as submitted a report to the bug bounty service Zero Day Initiative that said update showed that the vulnerability failed. The discovery prompted Microsoft to develop a new patch. The result is that it was released on Tuesday. ZDI has a complete breakdown of the failed patch here.

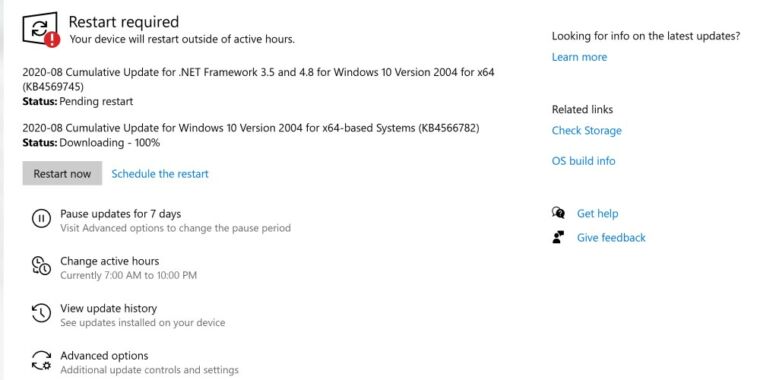

Overall, this month, nearly three-dozen vulnerabilities that were critical and many more with lower ratings plagued Tuesday. Within a day or so of release, Windows automatically downloads patches and installs them at times when the computer is not in use.

For most people, this automatic update system is fine, but if you’re like me and want to install it right away, it’s easy too. On Windows 10, go to Start> Settings> Update and Security> Windows Update, and click Check for Updates. On Windows 7, go to Start> Control Panel> System & Security> Windows Update and click Check for Updates. A reboot will be required.